Four days after Christmas, 1880, two businessmen working in the food trade at Hibernia Traders, Borough High Street, London, stood in the dock at Mansion House charged with hiring a prize-fighter to cause bodily harm and mischief to a third trader, Timothy Horgan.

Horgan (sometimes reported as Hergan) was an Irish man with large whiskers and a bacon dealer who had narrowly escaped being disfigured with knuckledusters by Constantine Morris, plasterer, pugilist and – as you will see in this article – a general ruffian from the Midlands.

The defendants, Edward Hipwell, 28, and Edward Rayner Hume, 40, were well known men in the City of London. They had been engaged in a longstanding, bad-natured, debate with Horgan about the quality of some bacon. County court action had not solved matters. A violent scuffle between Hume and Horgan upon exiting the county court had not solved it either.

Hume had variously called Horgan an Irish bogtrotter, an Irish cannibal and a coward. Horgan told Hume that he was an atheist, and a divorced scoundrel, who should go and see to his wife. Then he bit him. Things were getting nasty.

So in October 1880 the defendants placed a wanted advert in the Sporting Life calling for a “heavyweight boxer” to come down to London for a particular purpose. They might have described it as “business (private)”, sure, but they basically advertised, publicly, for a hitman. Not to kill Horgan, but to rough him up something rotten. To “let him have it”.

While sitting at home in Sunderland scouring the Sporting Life (probably for prize-fighting opportunities, since the newspaper was still very much aiding, abetting, and facilitating the practice), Morris had spotted the advert and enquired as to the nature of the mysterious task at hand, and how much money it was worth. His first letter asked whether the advert signatory (“O.P.Q.”) was trying to arrange a fight, because a fight is what Morris wanted.

Numerous letters passed between Morris and the defendants, and Morris then travelled down to London and took a room on Victoria Dock Road. As arranged, he arrived at the Monument on Fish Street Hill in the City, down the road from the Crosse Keys Wetherspoons, where I started writing this piece last week. He had, as requested, put a scrap of white paper in his buttonhole so that he might be recognised by Hipwell.

Shortly after the arranged time, on the arranged morning, Hipwell approached and asked if he was Morris. Yup, nodded Morris, and are you O.P.Q?

Morris followed Hipwell to the Shades Hotel at the Old Swan Pier just a few minutes walk away, and the party ordered drinks and entered a private room. According to Morris, Hipwell provided further detail that had not – supposedly – been provided in their prior written exchange:

“A friend of mine [Hume] has been assaulted by a dog of an Irishman, with big whiskers, and I want you to follow this friend about and at a signal, which I or my friend will give you, I want you to come forward and hit him with a blow from a life preserver or a knuckleduster, and when he is down, to beat him well.”

Morris was promised £20 if he completed his task, but queried what would happen if he was locked up. The money will be sent to your house, Hipwell confirmed. Morris started to get cold feet, stating that it seemed quite a hazardous task, and he would like to have his brother with him. The brother could be seen by Hipwell through the window, standing outside the hotel, freezing and looking shifty.

Morris was offered a £3 down payment and the men exited the hotel. Hipwell went off to meet Hume, Morris and his brother following a little behind so that they could see Hume from afar, and Morris would then be able to recognise him when they next came to meet and complete the task at hand.

Things get a little blurry at this point, but it appears that Morris and his brother spent several days and nights lurking around a railway arch on Tooley Street waiting for Hume to exit his business premises. When they eventually spotted him, alongside Hipwell, they went over to meet them. Hume repeated the instructions, regarding the Irishman: “Give him a good thrashing, make sure to disfigure him well,” Hume allegedly told Morris. Hipwell gave Morris another £3.

Morris spent the next few days writing letters to the defendants, demanding more money, but did not receive a response.

So Constantine Morris and his brother went and ratted everyone out to the police, claiming they never had any intention of carrying out the attack. Morris admitted that he had pocketed the money, demanded some more money, and then decided he wanted to expose the defendants for fear that someone else may be persuaded to attack Mr Horgan and he might lose his life.

Hume and Hipwell, despite the best efforts of their lawyers to prevent City gentlemen of good standing being imprisoned, were taken into custody, their trial set for the Old Bailey on 11 January 1881. Morris was set to give evidence for the prosecution.

The defence argued that Hume had been repeatedly insulted by Horgan – who had even bitten him. Plus, neither Morris brother was a reliable witness, or more precisely, they were “utterly unworthy of credit”, prizefighters and ruffians as they were. Numerous men of high standing came forward to give good character statements to the defendants. A jury swiftly found the City men not guilty, to a round of applause in court. Everybody went home, free men.

Constantine Morris might have been born in Birmingham in 1854. As a young man, he found work as a plasterer. In 1876 he was the victim of a violent assault, his watch and chain (worth £1) stolen by a screwmaker, a printer and a bricklayer with Irish surnames after the four men had been drinking at a pub called the Anchor Inn. Morris was hospitalised with a head injury, but did manage to get his watch back.

In 1877 Morris was arrested for being drunk and disorderly near to his home on Nova Scotia Street, Birmingham. A report in the Birmingham Mail described him as “acting in a very violent manner, knocking men and women down on the ground”. Upon being taken into custody, he continued to be very troublesome. Several prior offences were noted by the Mail. Morris was sent to prison for a month.

Morris, who had lived at three different Birmingham addresses in three years (as well as prison) was back at work plastering in 1878, before being charged with stealing bottles of alcohol from the pub he had been working in.

George Brookes of the White Horse had arrived back late on Good Friday and went to inspect Morris and his colleague Wright’s work. Both plasterers were plastered, having helped themselves to champagne and spirits from the landlord’s stores. Wright told the police that he’d been pressured into stealing and drinking booze by Morris, who had threatened to whack him around the jaw if he didn’t. Morris said that Wright “wasn’t right. He’s a fool at work”, and both men pleaded guilty. Wright got seven days, Morris served three months with hard labour.

Whether Morris really kept out of trouble or if he just kept out of the newspapers between 1881’s incident in London and 1897, I am not sure at present. There is some indication from records that he might, like many other people at the time, have emigrated to America and gone to Chicago, and he might have married a woman called Margaret while there. It is here that I believe he became a prize-fighter, but with time and source access limited to me at the moment I’ll have to dig into it all later.

Eiither way, he was in Britain, or back in Britain, by 1897.

In 1897 Constantine Morris almost cut a man’s ear off with a razor.

Morris, still a plasterer, had moved to London by this point. I believe it to be the same man, given the unusual first name matching with the occupation and similar age – in press coverage of the stabbing his age was given as 39 (which places his birth date at around 1858, rather than 1854 as records suggest).

The “big brutal looking man” was charged with wounding a Robert Spencer, labourer, on his right ear. In court, Spencer said that on a Saturday night he’d been stopped by a woman who asked him for directions. While he was talking to her, Morris approached, and the scared woman told Spencer that Morris had been knocking her about. This angered Morris, who said something along the lines of “what right have you to be here?” to Spencer. About as much right as you have, came the reply, before Morris adopted a fighting stance and told Spencer, his fists raised, that he’d “show him how they serve them in America”. Then he took out a razor blade and slashed at Spencer, cutting his ear and side of his neck (nothing too bad, just the three stitches needed later, but apparently he was very close to losing the bottom of the thing and the neck nick could definitely have been worse than it was).

Morris started acting weirdly, yelling Police! and Murder! like he had been the one hurt. Spencer was certain he was intoxicated, which sounds about right. In court, Morris claimed Spencer had whacked him around the head with a piece of wood but there was no evidence to indicate he had, and Morris was remanded into custody.

After moving to Canning Town the 41-year-old plasterer was arrested again in 1899 for assaulting James William McGregor, secretary of the Rhodesian Company in Plumstead. Having travelled on the Bexley omnibus, the two men got into an argument as they exited, and Morris punched McGregor in the face. In court, Morris again claimed that McGregor was the initiator, and he had only acted in self defence because McGregor had raised his stick to him. It was another month’s hard labour for Morris, the “bullying ruffian”.

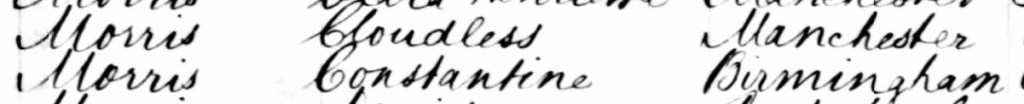

Constantine Morris is an unusual name for the place and time period. I found a Constantine Morris born in Birmingham in the fourth quarter of 1854 which seemed correct, given our Constantine is living there in the 1870s as a young (and occasionally quite drunk) man.

In October 1854 a Constantinus Morris was baptised in Birmingham. His parents’ names were Jacobi Morris and Birgittæ Gorman Morris.

But I have found no sign, yet, of a Constantine or Constantinus Morris living anywhere in Britain on the 1861 or 1871 census as a child and teenager, or on the 1881 or 1891 census. The prize-fighter and plasterer Constantine Morris appears to have been somewhat itinerant, although whether it was more or less so than anyone else of his age and profession, I’m not sure. He moves around a lot, between various Birmingham addresses, to Lichfield, Sunderland, London, and perhaps further afield. Might he have changed his name somewhere along the way, going by a middle name perhaps? Could he possibly have been from the Travelling community – they’ve never been, by and large, fans of a census.

I had also found a Charles Constantine Morris on birth records which prompted me to search for Charles Morris, born in the mid 1850s, in Find My Past and on Ancestry – it’s a much more common name. And here we might have an answer as to why Constantine doesn’t really exist, why we have few records of him and seemingly no mention of him as a prizefighter of any description (in available British sources) beyond the fact he was described as such during the 1880-81 court case involving the City bacon debacle and the Irishman.

On the 14 March 1877, we find in the Birmingham Mail:

“Charles C. Morris, plasterer, Nova Scotia Street, Birmingham (that’s the same street address as one of Constantine Morris’s in 1877), aged 23, was charged with violently assaulting George Gilbert… The complainant stated that as he was coming along Coleshill Street last night Morris came and struck him on the eye without provocation.”

Morris then kicked Gilbert and broke his arm. For the defence it was alleged that Gilbert had assaulted Morris’s wife.

Charles C. Morris and Constantine Morris, based on the name, the address, and the behaviour, really do have to be the same man. Unless there were two plasterers, both called C. Morris, living on the same road in the same year, with both being drunken thugs who liked to indulge in unprovoked violence. Doesn’t seem likely, even in Birmingham.

In 1878 a Charles Morris was picked up for vagrancy in Lichfield, which is not far from Birmingham at all, and imprisoned for two weeks as he was “not able to give a good account of himself”, and had been found sleeping in “a hovel”. Charles Morris is a common enough name, certainly compared to Constantine, but something about the reference to a nickname in an article published in the local paper stood out: the Charles Morris in the hovel was known as Lavender. Sounds a bit like a prize-fighter’s pseudonym to me.

But so far searches for Constantine, Charles, and Lavender with assorted search terms (prize-fighter, pugilist, and so on) aren’t proving fruitful. A Charles Morris, again from the Lichfield area, was involved in a case of prize-fighting in October 1877 – another man was arrested for fighting, and then violently assaulted a police officer, and a Charles Morris gave evidence in court. A George Morris was arrested for fighting in the same place, at the same time – which might have been coincidence, or could he have been the brother from the London incident of 1880?

There is a Constantine Morris on the 1901 census – a ‘plasterer builder’ from Birmingham with an estimated birth year of 1859, who was a patient at the General Infirmary on Southgate Street in Gloucester, England, and there are also Constantine Morrises born in the 1850s to be found on workhouse records in both North and East London in the early 1900s, who may or may not be relevant.

And there are a handful of Constantine Morrises in the United States in the Find My Past database that I currently have access to, including one who appears to have moved to America, having been born in England. The 1930 United States census shows an English 76-year-old with Irish parents called Constantine Morris, in Chicago running a boarding house. That same Constantine Morris was also in Chicago on the 1920 US census: an Englishman, born to Irish parents around 1857, and working as a plasterer.

That’s as far as I have time to take it now with Constantine Morris, the plasterer and prize-fighter.

It is a slightly dissatisfying end to a story which had no prize-fighting in it at all, largely because I can not figure out what on earth this man’s real name is and whether he ever fought under his real name, or even fought much (in a boxing ring) at all. Had he left for America in the early 1880s and made a name for himself there with the fists, before returning for a while, then heading back? Possibly.

It is interesting to note that, like many others, Constantine’s ‘profession’ as a prize-fighter, pugilist or ‘professor of fisticuffs’ as one newspaper termed it, was widely used by newspapers when describing him in the 1880 court case: that’s the same year that the Home Secretary issued a directive to magistrates to crack down on prize-fighting. Much of the press – Sporting Life aside – were extremely keen to paint anything to do with bareknuckle boxing with a black brush. It makes for much juicier headlines to have a prize-fighter involved in a scandal, than a plasterer.

This story might not have had any in-ring action. Sorry. But come on… I did provide an Irish bacon trader with large whiskers biting a man who called him a bogtrotter on the chin.

Leave a comment