In my first article on Ching Hook I wrote briefly on the murder of Hook’s close friend and trainer Alexander Hayes Munroe, known as Alec or Aleck Munroe, Munro or Monroe. Born in Kingston, Jamaica in 1850 or ’51, he first appeared in east London boxing news in the late 1870s. He is listed on the 1880 census as a mariner, boarding at the George Inn on the High Street in Rochester, Kent.

In 1885, Alec Munroe was stabbed in his Whitechapel boarding house and died from infection in the London Hospital shortly after.

I regret not giving him his own article – this story most definitely deserves it – but I do intend to expand further on his life and death in whatever future book I produce. The National Archives have kindly provided dozens of pages of witness statements from the trial of Munroe’s killer, and there is also so much more to write about his boxing years. A number of newspaper reports on his death (referring to Alexander Hugh Munroe), also reference his work as a lion tamer. No photograph has yet been found, although I know that during his life, a photo or painted portrait was among those hanging in at least one East End pub, with the owner publicising his wall of images in his advertising.

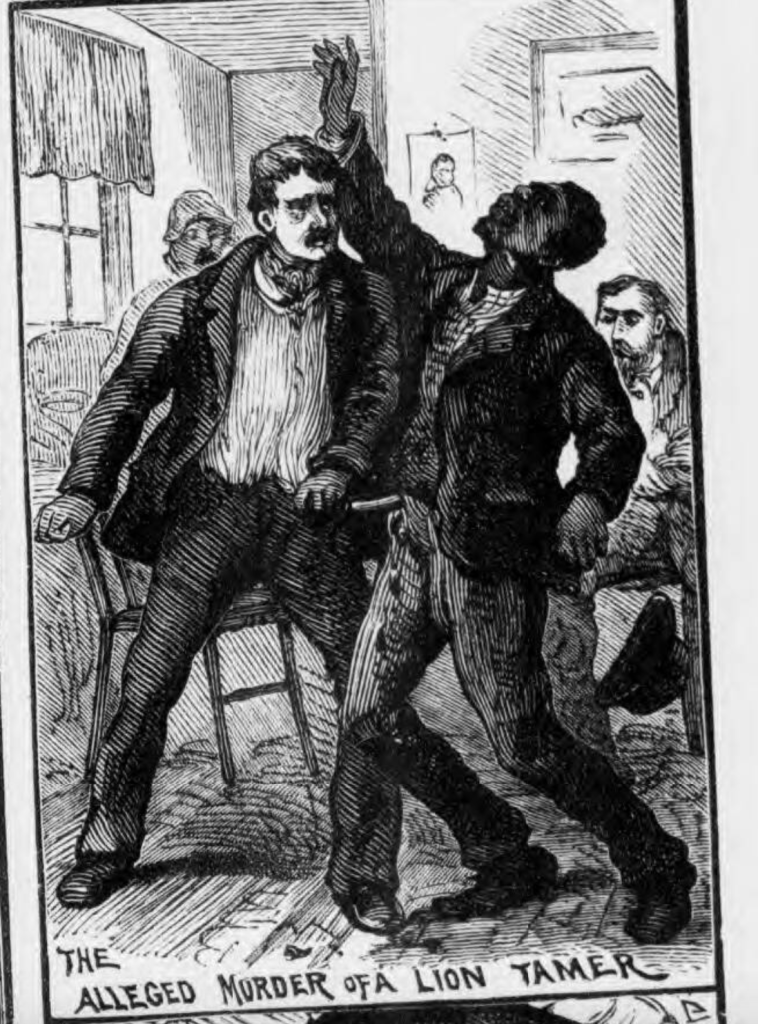

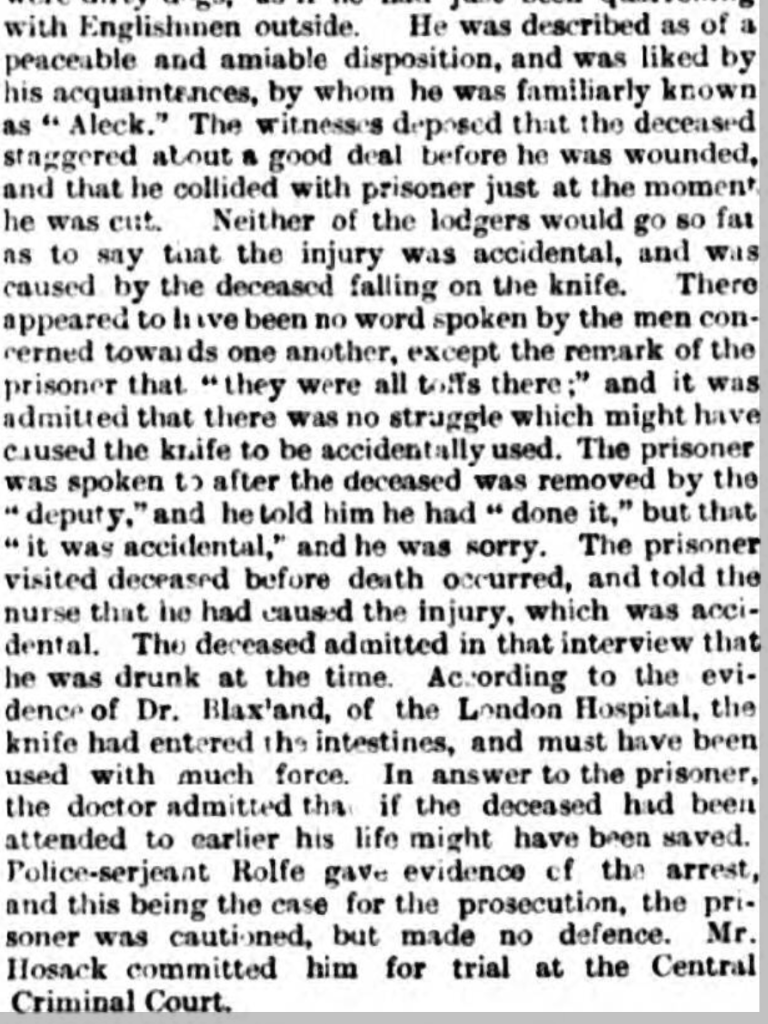

Update (18/02/2021): A sketch from the Illustrated Police News on 10th October 1885, showing Alec’s murder. The Police News wasn’t exactly known for it’s realism, so whether or not this is an accurate depiction of his appearance, we don’t know!

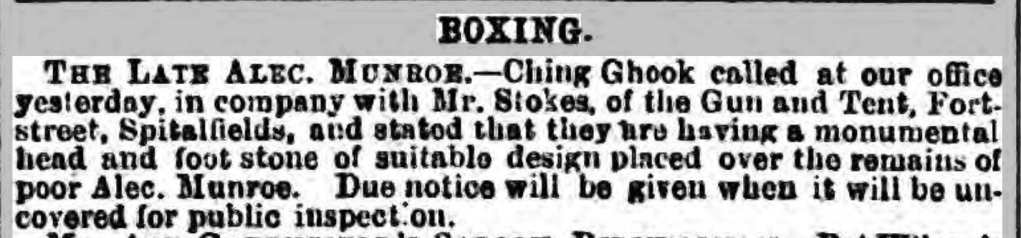

When Munroe was buried on the 13th September 1885 it was reported across London and Kent regional newspapers that 20,000 people (!) lined the streets of east London to witness the funeral procession. The Norwood News described him as “a great favourite with everyone in the neighbourhood” and his final resting place was reported variously as ‘Manor Park, Ilford’ or ‘Ilford Cemetery’. A few days later the Sporting Life carried a small story stating that Ching Hook intended to build a ‘monumental head and foot stone’ for the grave.

The search for my lads’ graves has often been sad and frustrating – where plot numbers usually exist, I can find the approximate area of burial, but there is never a grave marker to be found. Jack Wannop and his family have no headstone at Brockley, although there are some stone borders around the small plot. I have not (yet) found headstones for Dick Leary, George Brown or Warren ‘Dais’ Patte in Brockley either, although I know roughly where they are buried. Tom Thompson is in a Camberwell paupers’ plot with eight others, under bushes and weeds. Ching Hook disappeared in 1892, my intel suggesting he might have died in the United States. Jack Davenport’s final years are a mystery.

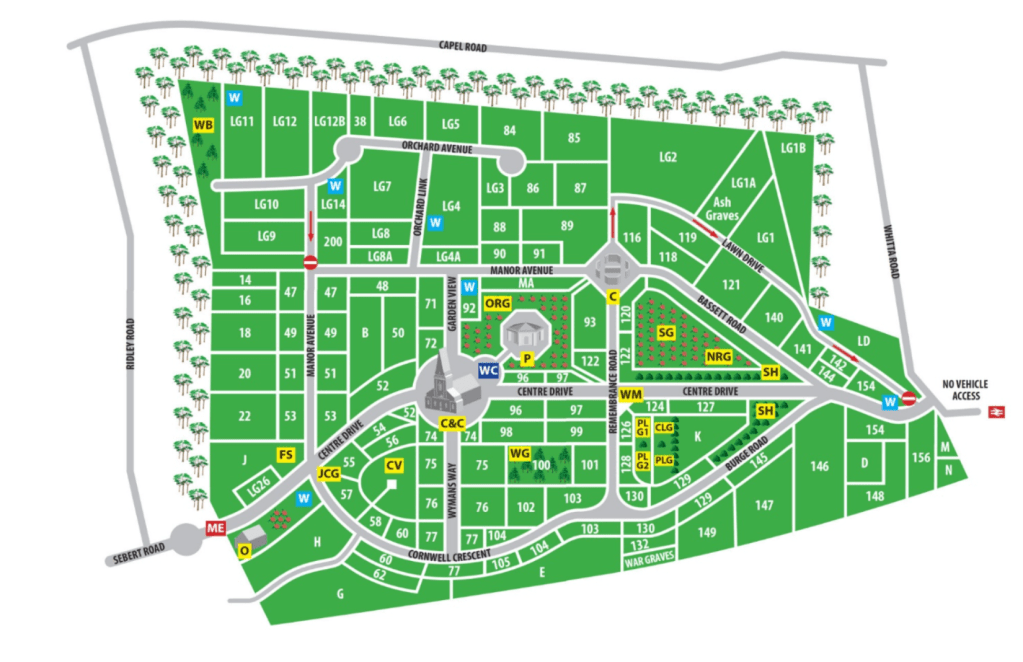

The records of the Manor Park Cemetery Company list Munroe’s burial in square 157 at Manor Park Cemetery in Ilford, which is not to be confused with Ilford Cemetery, a 45 minute walk down the road. In the 1880s this was a public burial area aka the paupers’ graves. Thousands might have known and loved Munroe enough to see him off, but he also died a single man living between squalid Whitechapel boarding houses. What are the chances that Hook got the job done and raised the money for his memorial?

Square 157 can now be found in Zone N on the bottom right corner of the modern map, up against the edge of the cemetery before you reach the railway tracks.

At first sight this area, as expected, does not contain any stones or markers at all. The ground is raised higher than the section next to it, which contains a mixture of Victorian and more recent graves. Zone N is built up because it contains several layers of paupers’ graves – a multi-story deathpark, if you will – and unlike the lucky residents to the right of the picture below, there’s nothing there to show who they were or when and how they existed.

That is, until you walk past some WW2 military burials and reach the far left corner of Zone N, right next to Manor Park Station. Here, nestled against a bush, there are three older headstones, barely peaking out from the grass. The piled up earth obscures all but the tops, and what is visible of the chiselled inscriptions of names and dates and platitudes is largely weathered away.

And here he is, among the hundreds of long dead and disappeared poor – Alexander Hayes Munroe survives. His name is obscured, the words on the right side of the stone faded away, but it is undoubtedly his. Ching Hook kept his promise, and it has lasted for 136 years.

This post was written with enormous thanks to super-detective Dr Ben Swift

Leave a reply to The Most Popular Man in New Cross (Introducing Jack Wannop to Carthorse Orchestra) – Grappling With History Cancel reply