This is the third and final chapter of Ching Hook / Ching Ghook / Hezekiah Moscow’s story. You can read the first part (which includes information about why I’m researching him and what on earth all the name variations are about) here and the second part here.

There has been a relatively huge amount of interest in my last few blog posts and tweets about Hezekiah Moscow, who was better known as Ching Ghook or occasionally Ching Hook. The latter is the first name I came to know him by and what I generally refer to him as throughout my posts just to try and avoid confusion. The photo which started all this, held in the National Archives and taken in east London in 1888, captions him as Ching Hook.

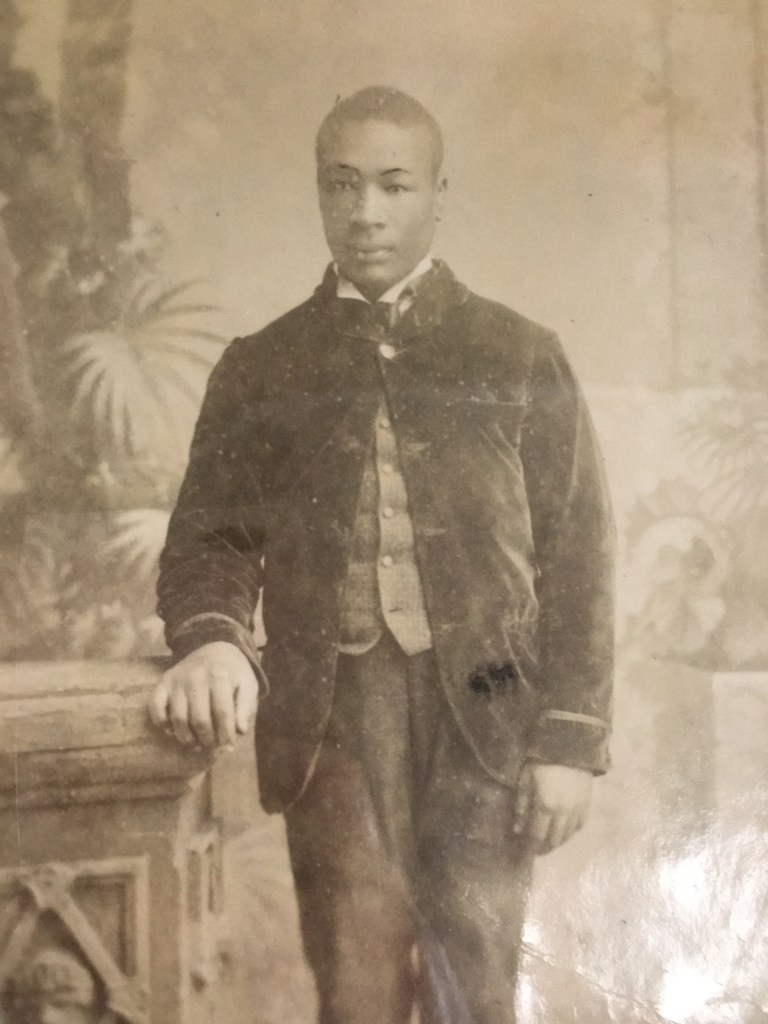

This weekend I went to the Archives to find the only other known photograph of Hook, in street clothes. And here we are! Complete with emphasised eyebrows, likely drawn on by the photographer. I believe this was done to make features stand out when the quality of the picture may have been poor, but it also gives him a theatrical air as befits a music hall star:

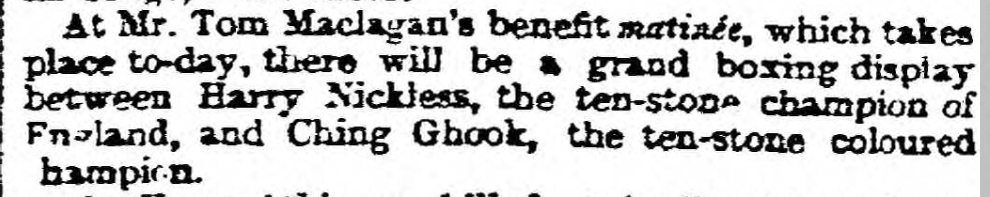

Hook was last seen by his wife Marian or Mary Ann Moscow on 30 March 1892. His most recent advertised appearance had been at the Polytechnic Boxing Club on Regent’s Street Fifth Annual Assault-at-Arms on 4 March. On Thursday 7 April, Hook was due to appear, sparring against Harry Nickless, at a retirement benefit at the Oxford Music Hall for entertainment legend Tom Maclagan. The Stage promoted their appearance in advance:

Tom Maclagan’s farewell party was widely covered by the London and theatrical trade press, with reviews appearing in the Evening Standard, The Stage, the Music Hall and Theatre Review, The Era, the South London Press and the London and Provincial Entr’acte but among a huge and diverse line-up of acts Hook and Nickless do not appear at all in the write-ups, suggesting they were a no-show. The Stage even had a swipe at advertised acts (particularly 20 “well-known ladies”) who failed to materialise:

As an aside, Maclagan asked the audience at his retirement benefit whether he should actually retire, and when they vehemently yelled no, decided to give them what they wanted.

In July, Marian Moscow posted a terribly sad notice in The Sporting Life newspaper requesting information on her husband’s whereabouts, and she called on the boxing fraternity in the hope they will help her. She was alone, had little money, and the Moscows’ daughter Eliza was just one year old. I am not sure what to make of the three-and-a-half-month gap between her last sighting of him and request for help but I do have three broad theories as to where Hook went, albeit with very little evidence to support any of them. I thought it might be worth jotting them down for consideration.

As always, if you have ideas or questions (or ideally hard evidence!) please do get in touch via the comment section below or Twitter.

Theory 1) He was murdered, died accidentally, or killed himself on or shortly after the 30 March 1892. As previously mentioned, there are no hospital or death or burial records for Moscow or any of his pseudonyms. His name appears on the 1895 school enrolment of his 4-year-old daughter as the registered parent, but that doesn’t necessarily mean he was alive – Marian could still have been hoping for his return. She is described as a widow in the 1901 census but may have declared this rather than admit her husband had left her.

I have searched the newspapers, using as many phrases as I can imagine, for any sign of foul play, as Marian in July 1892 believes Hook may have come to harm rather than simply left her and their daughter. Yet why would anyone have killed him? He was by all accounts a well-liked, well-connected, popular man. If he was killed, for example, in some similar circumstance to his best pal Alec Munroe (stabbed to death, drunk, in a Whitechapel boarding house), could his body have been buried, and permanently disappeared? It’s not exactly something that’s easy to do in the middle of London.

There are a small number of dead men washed up in the Thames over Spring/Summer 1892 or found elsewhere on, for example, hills in the north of England. Most are identified straight away or shortly after. A couple do not appear to have been named, and one from the river is described as so badly decomposed as to be unidentifiable. Another has the “appearance of a solider” and was around 5ft 8. While black Londoners had increased in number over the 1870s and 1880s they were still not a large enough population for a corpse’s skin colour not to have been remarked upon in the newspaper as a potentially identifying feature alongside hair colour or height, should the body have been black and should the body have been in a state where it was possible to identify race. I also believe Hook to have been around 5ft 6.

Having said that, I’ve gone as far as to discuss this with a mortician (it’s amazing having friends I can send this sort of weird Whatsapp message to…), who has told me that even after just a week submerged in water, a person’s features and skin colour could become difficult to identify. Hook was retrospectively said to have enjoyed a drink (did he go on a bender, gone very wrong?) and had been hospitalised twice previously to my knowledge – once for a condition unknown, and once for abscesses to the thigh. But surely word would have got back to Marian and/or the police if he had been injured or killed. Overall, this theory seems unlikely.

Theory 2) He ran away – perhaps with another love interest – and changed his name, settling somewhere else in Britain. The 1904 article which explains how Hook was given his nickname, also notes that his boxing career was cut short by the attractions of the “pewter mug and the fairer sex”. He had married Mary Ann or Marian in 1891 and their daughter was nine months old at the time of his disappearance. Had he met someone on 1891’s music hall tour, as he performed with Alice Daultry and Corporal Higgins and gone to join them in another part of Britain? Would he have given up his music hall work and boxing career for them, and if he did, why could he not be found by the police – who had been alerted to his disappearance – or identified by a member of the public? As Ching Ghook he had toured the country regularly as a boxer and boxing instructor, and lately as a music hall artist. He wasn’t famous by a modern definition, but he was ‘known’. Could he really have remained incognito?

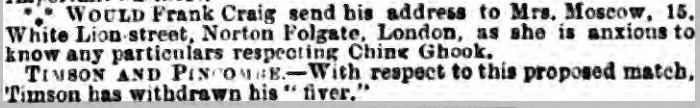

Theory 3) He moved to New York but Marian didn’t find out for a while. Now, hear me out. In 1896 – four whole years after Hook disappears – his wife had a note published in The Sporting Life for a Frank Craig, asking for Craig’s address so she can find out “any particulars” relating to Hook:

Frank Craig isn’t exactly an unusual name and she could be referring to anyone. An Irish neighbour, in their predominantly Irish and Jewish neighbourhood, perhaps. But is it a coincidence that Frank Craig (1868-1943) is also the name of a well known black boxer and later music hall performer, who moved from New York to London in 1894 and fought on many occasions in east London, particularly at Wonderland in Whitechapel, and thus knew many of Hook’s boxing pals, including Bill Cheese?

And yet if Craig – who was known as the Harlem Coffee Cooler – had moved to England in 1894 and Moscow had disappeared in 1892, what on earth has this particular Frank Craig got to do with anything? How could they have known each other? Sure, this is perhaps extremely tangential, but Craig was from New York. He made his debut there as a boxer in 1891 and over the next couple of years fought largely in New York and occasionally Boston and Philadelphia.

Ellis Island officially opened as a federal immigration station on the 1st January 1892, three months before Hook disappeared and over the next 64 years more than 12 million immigrants passed through it. Hook, in his only appearance on a UK census gave his occupation as “Traveller”. Throughout his nine or so years in Britain he is based in the Norton Folgate area of East London but travels widely across England, as a boxer and boxing instructor and later as a theatrical sketch artist.

By the age of 30 he’s washed dishes, trained bears and lions as a circus performer, spent eight years as a pugilist, developed a successful comedy music hall act and had countless addresses and at least three names. As I’ve previously mentioned, I’m not even sure his ‘real’ name was Hezekiah Moscow. Would the siren call of a new life in New York have been attractive to a multi-talented 30-year-old man with itchy feet? Did he move to New York and get involved with the boxing scene?

Now imagine my surprise when I found that there is a H. Moscow from London on the Ellis Island records for 1892, arriving from Liverpool on the RMS Umbria, but there is little hard evidence to match him to Hezekiah. The name is logged in the ships’ records as Himan Moscow and his age as 35, whereas Hook would have been 30 or 31 if his age given on the 1891 census is correct. I am currently unable to read the passenger’s occupation (still working on it!). The passenger’s nationality is given as English, and while Hezekiah had lived in London for nearly a decade, he was born somewhere in what was then the British West Indies.

Interestingly, I cannot find any Himan Moscows on British records, nor Hiram Moscows, and while there are a couple of Hyman Moscows, none of their birth dates match up with this passenger’s, placing them at or near 35-years-old in 1892. The Umbria docked at New York on 6th August 1892 so would have left England at the end of July. On the small chance it was Moscow, what had he been doing all summer? And if Himan Moscow isn’t Hezekiah Moscow at all, and all the above is me just making wild assumptions (very likely!), could he still have travelled to New York anyway under a new identity entirely? Did Hezekiah Moscow become Ching Ghook who became Ching Hook who became John Smith or some other Tom, Dick or Harry? Is he there in American boxing reports from 1892 but under a name we’ll very likely never know?

And that, that is all I’ve got to go on, although I do intend to pursue this Frank Craig connection when time permits.

Thank you so much for reading.

Update: I have new intel on Moscow’s disappearance. This story has a new ending, of a sort! I’m saving it for the book though…

[…] <<READ PART III>> […]

LikeLike

Brilliant bit of research and great writing! Thank you 🙏

Is this the same Hezekiah Mascow (sic) who is recorded as having been born in 1864 in the Caribbean and entered a Barnardo’s home in 1882?

LikeLike

Hi Lesley… I’m not so sure, but it does sound likely. There are several transcription errors on Ancestry/Find My Past which have him as Heyekiah, for example, on his daughter’s school registration, and I’ve seen other Moscows transcribed as Mascow. I’d be so interested to see whatever documents you’ve seen though – this sounds really interesting?! The 1890 census has Hezekiah as being born in the Caribbean and the age written would suggest he was born in 1862 but these things are so often a few years out. Other than a marriage record to Mary Ann Maddin in Whitechapel in 1890 I’ve not been able to find any other ‘official’ documentation for him and thought this might be because Hezekiah Moscow might not actually have been his ‘real’ name after all – it could have been something he adopted upon arriving in London, for example (most Hezekiahs and most Moscows around seem to be Jewish). The first mention of him that I’ve found in the newspapers is May 1882, boxing as Ching Ghook, but I don’t know anything about his living situation until a bit later…

LikeLike

[…] Where Did You Go, Hezekiah Moscow? The Life and Times of Ching Hook (Part III: Some Final Thoughts) […]

LikeLike

Hello, I’ve really enjoyed reading your articles about Ching Hook! I just have two questions though. Do you know how many Black people lived in London at the time? And did his daughter Eliza ever marry and have any descendants?

LikeLike

Hi Kaylie, thanks so much for reading. Eliza married a Mr Thompson in her early 40s and I’ve not managed to find evidence of any children. Because I’ve never been able to find out whether Moscow changed his name on arrival in the US, or much about his life during this time at all, I don’t know if he might have remarried or had any other children there.

As far as I know, the black population of London was relatively small in the 1880s-90s (certainly smaller than in the Georgian era) and mostly male but it’s really difficult to place an exact number or percentage because race wasn’t a piece of information recorded on the census in 1881 or 1891, although country of birth is. Of all the black boxers I’ve researched, around half came from the West Indies and half from North America and most arrived as sailors around 1880 or the late 1870s before finding other work. I think ‘working class’ black London life is very under-researched, anyone outside those connected to Queen Victoria or your Samuel Coleridge Taylors, etc! This UCL map is quite interesting and there’s a good short reading list here too 🙂 https://www.ucl.ac.uk/equiano-centre/projects/black-londoners-1800-1900 – I’ve just started doing more reading on this myself and have been gifted the book ‘Black Americans in Victorian London’ by Jeffrey Green.

Hope that helps. Thanks again! – S.

LikeLike

[…] Where Did You Go, Hezekiah Moscow? The Life and Times of Ching Hook (Part III: Some Final Thoughts) […]

LikeLike

[…] Where Did You Go, Hezekiah Moscow? The Life and Times of Ching Hook (Part III: Some Final Thoug… […]

LikeLike