A page for other writing. You won’t find much boxing or wrestling here.

A content warning: the article below includes a description of child death by drowning

A printer and a printer’s son

My great grandmother Agnes Court (née Casey) was born in 1875. She gave birth to her first child in 1895 and her twelfth – that we know of – in 1921.

After Edward came Ellen, then William, Frederick, Agnes, Robert, Andrew, Ernest, John, my grandfather Alfred, Leonard, and finally Danny. Agnes was 20 years old for the first and 48 for the last – that’s nearly three decades of pregnancy, giving birth, recovering from giving birth, and trying to keep her babies alive. The family lived in a two-up, two-down, Victorian terrace.

I’m only in my 30s, but some of my great uncles and aunts were Victorians. The maths doesn’t quite feel like it should add up.

Whenever I want to complain that I’m tired or that I’m struggling with my son (just the one, one small, solitary, son, in a two-bed flat), I think about Agnes and what she probably felt like by the time Danny was born.

The Courts were all raised in Lambeth, South London, as most of the Courts had been before them for 300 years. John died in hospital in 1938, the same year as his father, my great grandad Frederick Court.

Frederick was a printing assistant for magazine and book publishers. I know that he had worked during the late 1890s and early 1900s for publisher and Liberal MP George Newnes, whose best known titles included Tit-Bits and The Strand magazine. In 1921 Frederick was still working on the presses, printing the magazine The Daily Graphic.

Several sons followed Frederick into the trade, but on the 1939 Register, my granddad Alf’s employment is described as ‘Insurance Agent’. We don’t really know what that was about. Possibly something dodgy. My mum knew him as a French Polisher and antique restorer who went on to own a south London sweetshop and then a hardware store in a posher bit of Surrey with my grandmother, Sally. He once gave a boxing annual to one of his nephews as a birthday gift and signed it from the ‘1938 Welterweight Champion of Battersea High Street’. That wasn’t really a thing, but it sounds good doesn’t it.

In 1939 he was living with three of his brothers – Danny, Leonard and John, all printing assistants, and their mother Agnes.

This essay is about the first born of my grandfather’s siblings, Edward Court, the son of a printer. It’s also about another printer who tried to save Edward’s life.

My research was inspired by the work of my former colleague and MA History supervisor Dr John Price, a history and heritage consultant (previously of Goldsmiths, University of London), who wrote the book on the ‘everyday heroes’ memorialised at Postman’s Park.

The hero in this story, Mr John Bannochie, isn’t among those remembered among the Park’s plaques to those who selflessly tried to save a stranger in need, but that’s why I’m writing this essay. To thank him.

If Edward had lived, he’d have been 26 when his youngest brother Danny was born. Edward probably would have been a printing assistant as well, if he’d survived the Somme, or the Spanish Flu, or whatever else killed off vast numbers of young men born, as he was, in 1895. He might have had kids of his own – quite a few, if family tradition continued – all Lambeth born and raised too.

My mum vaguely recalled my grandfather mentioning that he had a brother who drowned in the Thames. In her recollection it sounded like Alf had been there to see it happen. But when John Court died in his 30s, he died in hospital, and every other sibling bar Edward passed away in their 60s or 70s. So it had to be Edward who drowned. But he was born in 1895 and died on Thursday 6th September 1906 – 10 years before Alf was born. Of course, memories get muddled over time. That’s why we do what we do as genealogists and historians.

On a hot day, in the height of summer, Edward had done what any number of poor young boys without indoor plumbing or any sense of danger or disease did in 1906: he went for a swim in the Thames with his mates.

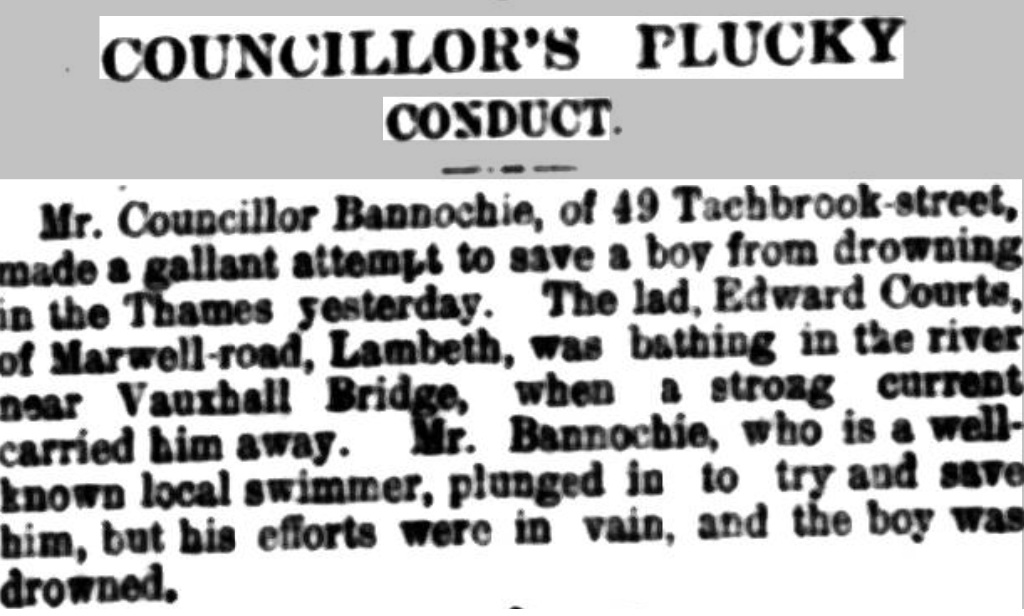

As reported in the Westminster Gazette, Edward entered the water from a mud bank with “a number of other lads”, swum out some distance and got into a strong downstream current. He was carried swiftly away.

Edward’s death went out on the newswires and because the same wire copy was used across dozens of newspapers, information about him was misreported in seemingly every regional and London paper in the land.

His surname was reported as Courts, not Court, and his age as 14 or 15. In fact, Edward Court was barely 11.

His address was given as Maxwell Road (the family lived in Maxwell Terrace). Edward reportedly drowned ‘opposite Daultons, Lambeth’, which we can assume to mean the Lambeth factory of Royal Doulton pottery. They had operated on Lambeth Walk for decades, before building a pipe factory in 1846 on what is now Albert Embankment. It is long demolished but if you walk away from the river a little, you will still find the former grand Doulton headquarters on the corner of Lambeth High Street.

The reports on Edward’s death were as inaccurate and short as you might expect yet another report of yet another poor boy dying in an accident to be.

Most did not mention that there had been a rescue attempt, but a few did. “A passerby quickly took off his outer garments and plunged in to try and save the lad,” said the Westminster Gazette. He was unsuccessful. An LCC steamer then circled around for a while to try and find Edward’s body but could not locate him. Edward was recovered later, and buried in Lambeth on the 15th September.

A couple of the London newspapers gave a name for the man who tried to save little Edward: Mr Bannochie.

This Scottish sounding name was and still is rare, even in a city as big as London. Through census records and the newspapers, it did not take me long to find a Bannochie who was likely to have been in or around Lambeth in 1906 and of an age where he realistically could have dived into the river to search for a young boy. I later found an article in the Westminster and Pimlico news which confirmed it to be the same man I had identified: a local councillor, and a well known swimmer.

John Mackie Bannochie was born in Westminster, London, possibly on the 3rd April 1871 – there are some inconsistencies in the records – the son of a tailor also named John Bannochie. John Bannochie senior was originally from Elgin, an historic town in Moray, Scotland.

Just a quick tangent. In the 1800s Elgin had been home to another John Bannochie, who may or may not have been a relative – perhaps an uncle – to John Senior and a great uncle to John Mackie, but I’m not sure. There is a whole essay to be had in this fascinating character. When he died from drowning in 1888 (from the exhaustion of being in his bathtub for too long, apparently!), Elgin’s John – who was originally from Aberdeen – was described in the local newspapers as among the best known people in town. He had won himself a great deal of notoriety at local political meetings for being a chronic heckler, repeatedly, noisily interrupting pretty much anything, constantly. The Last of the Hecklers, ran the headlines.

This elder Bannochie sounds like he was something of a hermit (“he rarely shows his face in public, except at election times”), unmarried, a cabinet maker who lived simply but had amassed £1,000 in savings. One obituary says that he did not have any children, but his political interests and passions seem wonderfully relevant to the youngest Bannochie in our story, John Mackie, and I can’t help wonder if they are connected. Anyway –

John Mackie Bannochie grew up on Tachbrook Street in Westminster with his parents and siblings, Mary and James. A brother, Thomas, had been born in 1877 and died in 1881.

The 1891 census shows John Bannochie, aged 18 (although I place him here at 19 or 20) and a printer and compositor, still living with his parents John and Jane, and with Mary and James and another sister, Margaret. Margaret was born just a couple of months after Thomas’s death.

In 1898 John married a Phoebe Charlotte Sophia Cox – no known relation to myself. Her surname was written down as Cocks on the marriage banns. It happens. They had one child together, May, then Phoebe died in 1901, aged just 30. She was buried in West Norwood Cemetery.

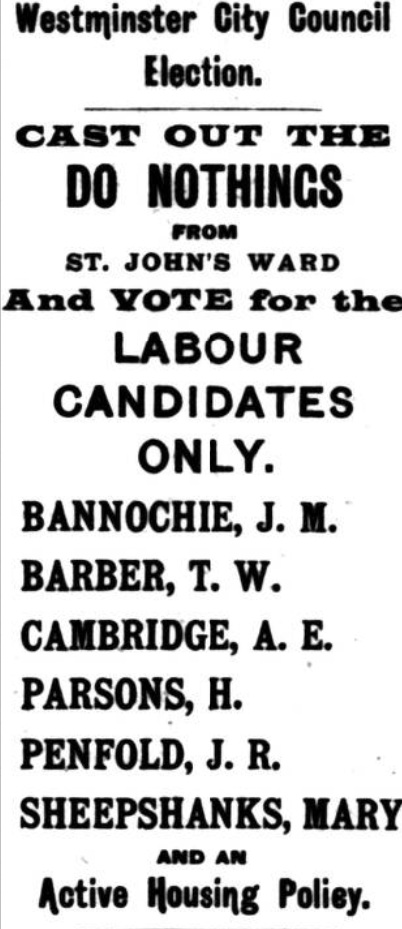

At some point, John (a printer and typesetter by trade) had joined the Independent Labour Party and was elected as a councillor to Westminster City Council.

Lively write-ups of council meetings published in the Westminster & Pimlico News give some sense of his character and beliefs. In 1904 we find him arguing in favour of a minimum wage for Council employees. A motion had been forward that a fixed sum of 30 shillings per week should be the minimum offered to all employees in Council services. Mr Bannochie and a colleague stood up in favour, despite arguments that the sum was above average, and too generous. “But few men on the Council should want to live on 30s a week,” he argued. The minimum wage scheme was rejected.

He joined a 1905 debate on the Sale of Whisky Bill, the object of which was to ensure that purchasers of the beverage had a clear statement on how it was made. Mr Bannochie was in favour, anxious that those who drank whisky should have the genuine article. “It livens one up a bit,” agreed his fellow supporter, Mr Everitt.

John Bannochie campaigned for more land to be purchased by the council to build housing for the working classes, and in a 1905 debate on taxation of land said:

“Landlordism is to a large extent responsible for a great amount of the misery encountered in this country.”

At a 1905 City Council meeting attended by the Mayor and Aldermen, with most attendees resplendent in scarlet robes, John Bannochie and one or two left-leaning others refused to dress in formal attire.

His elocutionary style was described as “rugged”, rather than clever or fluid, but young aspirants to political fame could learn a lot from listening to him, according to the local newspaper.

A few weeks after John entered the water to try and save my great uncle Edward, he travelled down to Burnham-on-Crouch, Essex, and took part in a City of Westminster Swimming Club competition. He lost out on the trophy but made a valiant effort in “the rather lumpy sea”, finishing second to a Mr Kirk.

Shortly after his return, “Comrade Bannochie” spoke at a council meeting on the unjust situation at the public baths, where the workers (the second class bathers) were subsidising first class facilities by paying their entry fee while being forced to swim in the dirty water of the first class bathers. A more equal system of swimming and washing facilities for the workers appears to have been one of John’s special interests

At the end of the year, John stood for election as a Socialist Party candidate for St John’s Ward, Westminster, jumping ship from Labour. On election day he stood at the gates of St Stephen’s School and yelled at all who would listen to “vote for the workers”. It was an ill-advised move: he was not re-elected to his seat.

By 1907 he had seen sense and returned to Labour and over the next couple of years we can find him speaking at a meeting of the Ealing Independent Labour Party, the Islington, Westminster, Brixton ILP branches and others too. One of his lectures was titled Socialism, Free Trade, Tariff Reform and Lower Income Tax. He appears to have been popular: the West London Observer in July 1907 observed the rise of Socialism in Hammersmith, with speakers such as Mr J.M. Bannochie addressing “large meetings”. “Socialism is in full swing,” the article said, the audience “desiring to know more of the doctrines”.

He stood again for Westminster Council in the 1909 election as a Labour candidate but I can not see any sign that he was returned.

On the 1911 census we find 39-year-old John Bannochie, a widower, a compositor, printer and linotypist, back living with his parents on Tachbrook Street, with his daughter May, 11.

John remarried later in 1911, to an Ada Whittaker from Lambeth – the same part of town as my family. Young May lived with them for a while but on the 1921 census we find her staying with her elderly grandparents, John the tailor and Jane. At 21 she was working as a teacher. Travel records from the 1930s for a May Bannochie born in 1900 – I believe it to be the same one – show a world traveller. She’s in Egypt one year, Burma the next, Japan, Portugal. By the age of 40 she was still single, without children, lodging with another female teacher in the home of an ‘Egg Collector’ (!) in Lincolnshire. I like the sound of May.

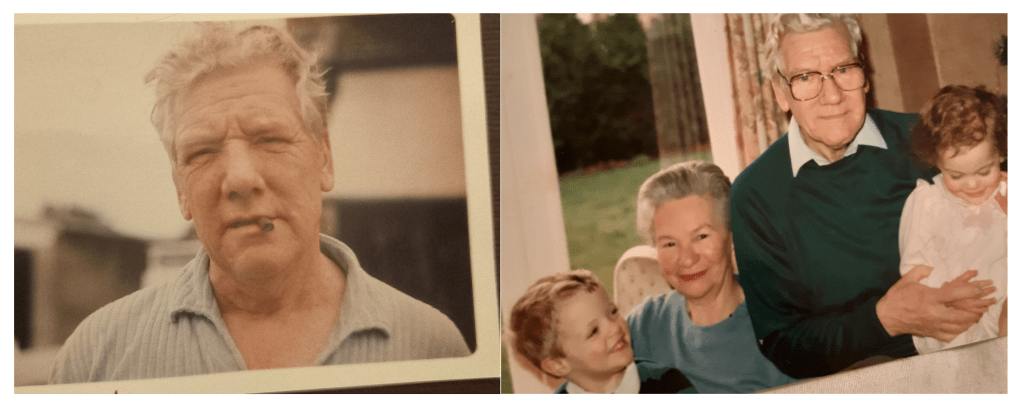

John’s second wife Ada died in 1938. The 1939 Registry shows John, twice widowed, a retired linotyper (the operator of the device used for typesetting), living alone at number 34 Lysias Road, Wandsworth, a half an hour walk away from where my grandfather Alf, some of his surviving brothers, and their mother Agnes, lived.

John Mackie Bannochie died in 1960, a very old man, who had tried to do some very good things in his life.

I started writing this more than four years ago but have never had the time to finish. After the arrival of my son, Jack, in November 2023, I started to think about Agnes and her first-born, Edward, again and it seemed really important for me to get it done.

Part of this article was written in a pub in London, close to the Thames. The other half was written in my flat overlooking the beach and the sea, on a lovely warm sunny day. There’s a bunch of kids out there. It’s nowhere near hot enough, but some of them are sticking their toes in.

In a decade’s time, my son will be 11. It seems very far away, but they tell me it goes by in a flash.

Half of me hopes for Jack to be out there too, tanned and floppy haired, hanging out with his mates in the fresh air, messing around, swimming. Better that than sat in his room on a games console, right?

Half of me wants him to be one of those kids out there. The other half thinks of Edward, and of Agnes.