In my early articles about Albert Pearce – you can read Part I and Part II here – I briefly mentioned Pearce’s career as a cyclist, before he turned to boxing.

It had been difficult to find much out about his involvement with the sport. The UK sources available to me – I rely heavily on the British Newspaper Archive at the moment – did not provide much information. The discrepancy in Pearce’s name (he is sometimes referred to in sporting newspapers as Pierce) didn’t help, either. Despite being an American, who grew up in Chicago or close to it, American newspapers available to British researchers through the Library of Congress archive did not provide much information.

Having read my first posts on Pearce, in stepped extremely helpful cycling writer and historian Feargal McKay who, in addition to being very knowledgeable about professional Victorian bike-riders and knowing where to look for information about them, also possesses the power to translate French.

In this final part of Albert Pearce’s sad story, I have attempted to piece together his final years (Part II finished in 1906, with Pearce blind, and in his early 40s) but I’ll go back to the start, first, and give Pearce a new beginning, based on McKay’s findings.

Please be aware that this article may contain language quoted or screenshotted from Victorian newspapers which is considered offensive today

Why are Albert’s early 1880s years and his cycling career so important? We know that during the decade he was one of many Black boxers in London and the North of England, but as McKay explains it to me: as a Black cyclist in Britain during this decade he seems to have been unique.

In my efforts to research and write the story of a boxer, I’ve accidentally stumbled across one of the first, if not the, first Black man to compete in British professional cycling races.

We know that the US had Black cyclists, including a club solely for Black cyclists from the late 1860s, but neither McKay nor I have managed to find evidence of non-White competitors on British soil before Pearce.

Black American cyclist Marshall Walter “Major” Taylor was a world record-breaking sensation who competed in England and mainland Europe during the 1900s, and his story is well chronicled. Albert Pearce was not a world record-breaker, or a sensation. But he was here many years earlier, and I have not been able to find evidence of a Black cyclist competing in English events before him. If you have evidence to the contrary, we welcome it.

Through McKay’s research we can place Albert, then still in his late teens, in Chicago in 1879 and 1880, race-walking. He was bike racing in Williamsburg, Long Island in August 1880 and we find him resident in New York during the summer of 1881, and cycling in Boston.

McKay’s findings then show Albert to have come to England several years earlier than I had initially thought – he looks to have arrived at some point in early 1882. Almost every Black American and Caribbean boxer I have researched so far seems to have arrived here between 1879 and 1882 – we’ll probably try and look into why in my book – so this doesn’t surprise me. Pearce looks to have arrived in England with the cyclist Jack Keen, a top rider and bike manufacturer.

So what makes Pearce also unique here, in comparison to any other Black boxer in England I have researched so far during the 1880s, is that he actually came here to be an athlete (a cyclist), rather than docking as, for example, a sailor of some description, and then turning his hand to sports.

McKay has Pearce riding in several one mile events at least four Six Day Races across 1882 and 1883. What are Six Day Races, you and I (someone who is definitely not a cycling historian) ask? Well, they were cycling races that lasted six days. These extreme tests of endurance began in the late-1870s, when a man called David Stanton bet that he could ride 1,000 miles in six successive days, riding 18 hours a day. Most races during the early 1880s saw cyclists take to the track twice a day, for four to eight hours at a time, over six days. Still don’t think that sounds impressive? Try it on a high-wheeled penny-farthing.

I have said before that in the late-Victorian period that there was almost nothing people weren’t betting on. Whether it’s the madness of cycling for six days, or walking backwards from one pub to another with bottles on your head, nothing was impossible and novelty was king.

These six day events were sometimes competed on indoor tracks (eg. at the Agricultural Hall in London), where everyone rode around and around and around while lots of other people watched, and sometimes they took place outside. It all began in Britain but soon spread to different parts of the world, including Chicago, where a young Albert Pearce had grown up.

In the earliest British race, McKay found Pearce listed among 115 entrants for the Whitsuntide One Mile Handicap at Wolverhampton’s Molineux Grounds in May 1882 – the prize was £35, or the equivalent of about £5,000 today. As a handicapped race, Pearce’s starting position fell around the middle of the field. He doesn’t appear to have progressed past the first heat.

An aside: among his 114 opponents was a man named J. West, who was from Birmingham, and only had one leg.

The Whitsuntide meet also included a three mile race between Keen and Pearce for a prize of £5. Despite Pearce receiving a 320 yard start, Keen won.

A few days later, more races at the Molineux Grounds were announced, including a novelty race set to feature Albert. When I said above that the Victorians loved a bit of weirdness and there was nothing you couldn’t bet on. How’s this?:

“A Clown Bicycle Trick (one mile race on boneshakers) – F Wood (Leicester) and H Higham (Nottingham) will compete against two donkeys, ridden by CR Garrard (Uxbridge) and A Pierce (London), in clown costume.”

Sadly, my desire to recreate this scene in detailed narrative form on this blog will not come to pass: the clowns versus donkeys match was called off when bad weather heavily impacted attendance at the grounds. It didn’t seem worth the effort of dressing up and getting the donkeys out.

Pearce doesn’t appear to have been a top tier cyclist. In his 1897 book Vingt ans de cyclisme pratique (Twenty Years of Practical Cycling), H.O. Duncan, in between a steady stream of racism, refers to Pearce as “more of a pleasant companion than a first-rate rider”.

While Pearce was claiming the title of “Black champion” in the cycling world, or at least newspaper reporters were describing him thus, this was both an unofficial title (much like boxing, no international board of control existed at the time for cycling) and something Duncan believes Pearce was only suitable for as there was little in the way of competition among Black riders in the US or UK. Keen must have recognised a talent, or why would he have brought him all the way to England? However, during Pearce’s participation in a Six Day Race in the north of England, Duncan recalls Pearce crashing through a large circus-type tent which sheltered a 150 yard track, taking several other cyclists down with him on a bend.

It seems Pearce also realised that cycling might not be the thing to pursue long-term. Across 1883 and 1884 I have found several mentions of him in English newspapers as a long-distance runner – his third sport after cycling and race-walking. In November 1883, for example, an article in The Sportsman shows him (described as being from New York) matched with a Thomas Arthur of Gateshead, to run for three hours at the skating rink, New Bridge Street, Newcastle. In 1884 at the Victoria Grounds, again in Newcastle, he met Arthur for a five mile race, with Arthur conceding to Pearce a 600m start. At the end of the third mile, Pearce retired, in the midst of a thunderstorm, hopelessly beaten.

Pearce pops up in a boxing event report from Newcastle in 1884, in an exhibition match in front of 3,000 people, although he’s not a regular in professional boxing reports until 1887. I have found little about him between the 1884 race with Arthur and ‘87. From my understanding of Duncan’s memoirs, Pearce may have been acting as a cycling coach during this period (and boxing on occasion, training and getting some practice in). According to Peter Lovesey’s research, published last year in his book Black Athletes in Britain: The Pioneers, Albert also worked in a cycle factory – presumably Keen’s – during this period.

He had not enjoyed much success in the Six Day Races and was not making money as a result, Duncan took sympathy and engaged him as a coach on a fixed salary, all his expenses paid, with a twenty per cent cut of prizes won on top. “I had made a new man of him, and I never regretted our choice, for he was my most faithful companion,” wrote Duncan. “He accompanied me everywhere, and as he was remarkably muscled, he massaged to perfection.”

The young hopeful had failed to find glory in walking, cycling, or running, but was getting paid to rub down more successful White guys instead.

At some point between then and 1886 or 1887 he decided to turn his hands to a fourth sport – boxing – and I do wonder if he really wanted to, or if it was through some sort of desperation, or lack of other options.

It’s here that we can return to the parts of Pearce’s story that I’ve already written in blogs one and two, covering his late 1880s and early 1890s boxing career, and his descent into blindness and unemployment from 1894.

Duncan had returned to Paris and did not see Pearce again until 1894. In his memoir he recalls attending a private boxing event in France. Out to the ring stepped a Black boxer, and Duncan was surprised to see it was his old pal Pearce – by then struggling significantly with his eyesight. He was so short-sighted by this point that he failed to ward off the blows from his opponent – Ted Rich – and he was “soon put out of combat by a formidable ‘bag’ between the two eyes”.

Duncan continues: “The poor fellow never completely recovered his sight; I had him engaged for several months by Edwards, as trainer; but he could not see well and, although he had been examined in various hospitals in Paris, he had to return to London where he became completely blind.”

Read Part I and Part II of Albert Pearce’s story here

Albert Pearce was born in Chicago, Illinois, in 1862 or 1863 and I had believed he was the Albert Pearce buried in Putney Vale Cemetery, on the 7 January 1907. But no! Thanks to information from football historian Andy Mitchell: that Albert was a young child.

While based in different parts of Britain during his stay here, including Newcastle, Albert had spent much of his 1890s and early 1900s in the Putney area of London. We also know that he was reported, in 1906, to be experiencing a “dangerous illness”. I scoured the sporting newspapers of December 1906 and January 1907 but did not find a notice of his death or a full obituary, nor was I able to confirm anything through British death records on Ancestry.

There was little sign of Pearce alive after 1906, until I came across a brief article in a February 1908 issue of The Referee titled “For A Poor Blind Boxer” which shows that Peggy Bettinson (former boxer and co-founder of the National Sporting Club) was helping raise funds to support Pearce, and a donation had been received by “H.F.C”. Presumably Bettinson was not helping maintain a dead man. So perhaps I am mistaken – was Pearce still alive in early 1908? The wording of the Referee article, however, does not make it clear: it says that H.F.C. had recently donated but also that Bettinson had started the fund “some time ago”. Perhaps he started it in 1906 or 1907, and the Referee didn’t know whether Pearce’s mortal status had changed since.

If you have read this far only because of the actress and the sausage seller in the title of articles one and two, thank you for sticking with it. The actress would be Lilian, and the sausage seller – or probably sausage maker, actually, I just got over-excited about alliteration and hadn’t finished my research yet – was her husband. In my hunt for Albert I became ever more intrigued with Lilian.

She was born on 25 January 1893, two years after her brother and just a year or so before her father went blind. The relationship between Albert and Emma in the years between 1891 (when the about-to-be-married couple appear on the census as cohabiting, with Emma’s mother, and their newborn son William) and 1901 is confusing.

I haven’t been able to find Albert on the 1901 census but we can find Emma, her mother, Lilian and William. Bizarrely, they’re using the surname Young, and had moved from West London to Sculcoates in Yorkshire. It is definitely them: Emma’s still a dressmaker originally from Chiswick, her mum Emma Swannell is living with them, Lilian and William’s ages match up, and Lilian’s middle name is ‘D’. While William was born in London, Lilian appears to have been born in Hull, Yorkshire.

Albert is not with them at the time of the 1901 census and we know him at this time to have been living in London – there is a benefit for him in 1901 but we also see him write into the Sporting Life several times asking friends to contact him, and he gives his address as Bridge Road, Hammersmith (West London). So it appears that Emma and Albert had parted ways, whether temporarily or permanently by 1901, and may have been divorced. Perhaps she had then married a Mr Young, and the children had taken his name, although there is no Mr Young with the family on the 1901 census either. Had he died, or she’d married then divorced him too?

To add further mystery, when we jump forward to the 1911 census, Emma, William and Lilian are all back to being the Pearces.

William Albert Pearce, 20, born in Putney and now an unmarried engineer, is head of the household. Emma, 55, a dressmaker from Chiswick, is widowed – I had thought this to be because Albert is dead. But perhaps Mr Young, if he existed, was too. Lilian Dagmar Pearce from Hull is 18, single, and working in a tin works. The family have a servant called Lily, and then there’s another Lilian who is boarding with them and working alongside Lilian Dagmar.

It is all very confusing, but I found no evidence that Albert returned to America after 1906 and no definitive evidence that he died in England soon after. After reading my first version of this blog, I received a message from Andy Mitchell with some news: Albert Pearce was on the 1911 census.

My searches for him on Ancestry under Pearce, with his approximate birth date and birthplace hadn’t found him. Mitchell’s searches on a different records database did: Albert Pierce (with an ‘i’), 43 years old (I place him at about 49 here, and Lovesey suggests a bit older still), ‘Boxer, Now Blind’, was one of four male boarders lodging with Walter George Peacock and his family on Fulham Road. Peacock, a ‘Pork Butcher Journeyman’, his wife, and their five children, had taken in Pierce alongside a Bird Fancier, an Errand Lad, and a Servant to a Gas Company.

Lovesey places Pearce in Fulham workhouse in 1913 – I’m currently searching for documentation confirming this, and looking into what happened to Albert next.

But ultimately, it is a sad ending for the multi-hyphenate athlete, and a truly tragic one in comparison to the long lives lived by so many of the men I have researched (most recently Felix Scott, or Constantine Morris), who left the world in old age after decades of drunken abuse, assaults, prison time or wife-beating. Albert Pearce, to my knowledge, was pretty much dirt-free.

There are photographs of Lilian Dagmar Pearce on Ancestry, but they are on a private setting. I’ve reached out to an account owner – who I believe to be a granddaughter of Lilian but have not heard back. Whether she doesn’t want to engage or has missed the message, I’m not sure, but perhaps I’ll reach out again soon. Whether she knows of Albert’s full history or not, I don’t know, but I’m sure she can shed some light on my confusion over the Pearce to Young and back again name change, at the very least – and I’m desperate to see what Lilian looked like.

In 1914, at the age of 21, Lilian married James William Bates. The marriage was registered in Sculcoates, Yorkshire, in the last quarter of the year. On the 1921 census we find them at 24 Newington Crescent, Southwark.

Lilian and James, both born in Hull, had moved to London and Lilian was employed as an actress. James’s personal occupation on the census was given as “Cooked Meat and Sausage Factory” and his employer as “Sainsbury’s – Butchers and Provision Merchant”. I take this to mean he made sausages or managed the sausage-process for the popular shop chain. James worked at Sainsbury’s large Blackfriars factory, which had opened in 1934 to produce sausages and meat pies. It was converted into offices in 1972 and demolished in 2016. An article published at the time of the demolition on the news website London SE1 gives a variety of details involving pigs’ heads and grinding machines.

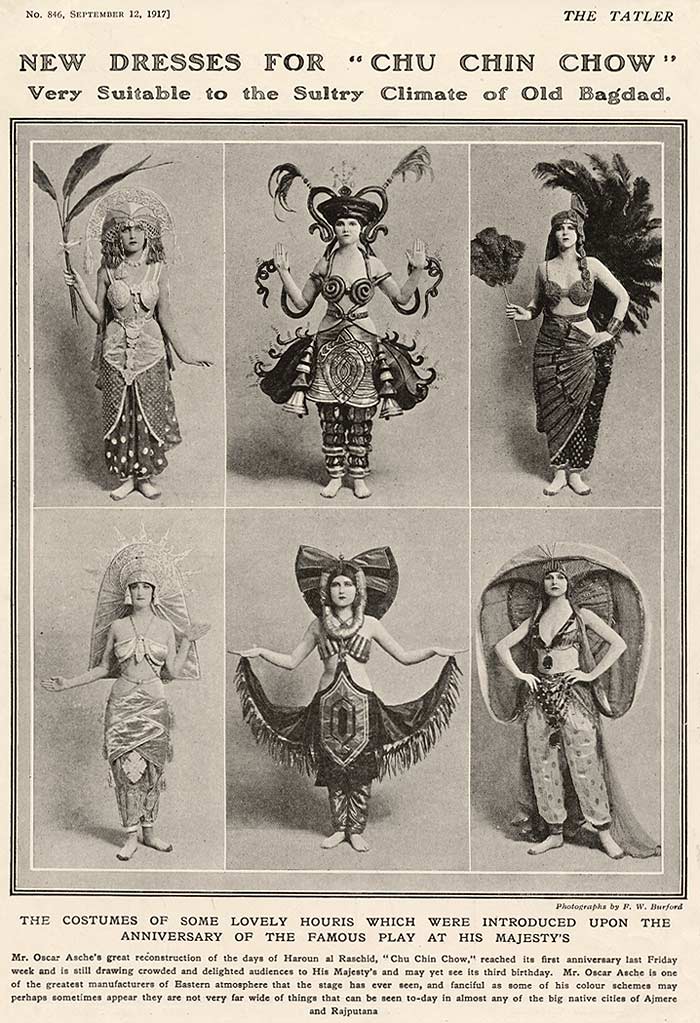

As an actress, Lilian worked for Oscar Asche, and at the time of the census in June 1921 was employed at His Majesty’s Theatre Haymarket. I’ve scoured theatre programmes to see which Oscar Asche productions were on there during this period but I’ve been unable to find a Lilian Bates (or Pearce, or Young) on cast listings. She likely used a stage name, of course, or had some kind of uncredited chorus role.

Oscar Asche – an Australian actor and director – was married to a Lily (Brayton – she’s much older than Lilian Bates). He’s best known for the production Chu Chin Chow, a big-budget musical comedy involving lots of White actors (and perhaps Lilian) in, well, you can probably guess from the title, yellowface. It opened during World War One and was on from 1916 – 1921 at the Haymarket. I cannot find Lilian under her real name as a cast member. Cairo, another Asche production, opened at the Haymarket in 1921. Again, no Lilian, and no actresses using a stage name that immediately jumps out as being her, but she may be among them. I’ll hope to find her – perhaps with the help of the relative on Ancestry – soon.

Lilian and James had a son, also James William Bates, who had been born in early 1920. On the 1921 census they were living with him and Albert’s widow, Emma Pearce, who was 65, and with no occupation.

A James William and Lilian Dagmar Bates of Geoffrey House, Southwark, London, baptised a daughter – Mabel Ivorn Bates – in November 1923. A 1933 electoral register for the area shows Lilian without James, but still living with her mother, Emma, in Bermondsey.

I’m not entirely sure whether it is her, but I have found a divorced Lilian Bates with an 1893 birth date on the 1939 Register, working in domestic service in Camberwell. A 14 year old girl called Marjorie Bates, born in 1925 is living with her, working as a machinist of some kind. A relative suggests on an Ancestry tree that this may be a daughter of Lilian, I think. The scanned 1939 Register has Marjorie’s ‘Bates’ crossed out and replaced with Kellman, with green writing above saying ‘cousins’.

I believe that Lilian Dagmar Bates, nee Pearce, died in London in 1972 and Marjorie Bates in 2011.

I am still searching for evidence of Albert’s death – I want to know when he died, and where he is buried.

Albert’s story has really gotten to me. The majority of the men I’ve researched have had at least one, if not multiple, brushes with the law for violence outside the ring – attacking police officers, sailors, random men in pubs, or their wives and girlfriends. There’s robberies too, murders, and lots and lots of drunken stupidity at various levels of illegality (and occasional hilarity).

Albert came to Britain from America, an athletic young man, wanting to make it as a cyclist. He turned his hand to running and walking. He’s the only one of the Black American or Caribbean born boxers I’ve researched who came to live in the UK to compete in sports. I have no arrests, and no outrageous drama, on his record. He tried things, didn’t do brilliantly, so tried more things, and then turned to boxing. He didn’t really do brilliantly at that either, but his clean-living, plucky spirit and determination make what happened to him even sadder: several of the drunk, violent, bastards in my work reached much older age. Albert was blinded in his early 30s, survived on charity for years, and possibly ended up in a workhouse.

It’s my (and cycling historian Feargal McKay’s) belief that Albert, after arriving here in 1882, might have been the first man of colour to compete in British cycling events – I’ve found no evidence to suggest otherwise, but welcome any information you might have which challenges us.

If there’s a second book in me, it’s got to be on Albert Pearce and the contrasts between his story and those of his meaner, badder, and somehow (unfairly) much less unlucky peers in the boxing world. He wasn’t a record breaker, he never hit glorious heights in any of his sports. But he deserves to be remembered.

Thank you to Feargal McKay for his enormous help with this post, to Andy Mitchell, to Peter Lovesey, and to Kevin R. Smith for the picture of Albert used in the header image.

This will be the last ‘proper’ research post on Grappling With History for a little while – you’ll find out why soon!

Leave a comment