Denny Harrington was a thief, a thug, a drunk, a dock labourer and a very well known pugilist, who was arrested, by my count, at least thirty-five times.

Many of the men I research, who boxed and wrestled in 1880s London, did very bad things outside the ring. They were tough guys, in a tough place and time. Some of it can be attributed to just too many beers, just lads being lads. Some of it is quite a lot worse.

Denny Harrington is at the more extreme end for number of arrests. But, admittedly, some of his record is also pretty funny. Harrington is certainly what we might refer to as ‘a character’.

Interpreting Harrington’s early years through inconsistencies in archived family records, newspaper coverage, and his criminal records is difficult. I believe he was likely born in 1850, although some sources suggest a few years later, some a few years earlier. He was named Dennis Harrington by his Irish parents, Mary and Daniel.

The couple’s eldest, Daniel junior, had been born in Ireland in 1849 before the family joined the wave of Irish migration to the East End in the early 1850s. The 1861 census suggests that Simon, Dennis, Patrick and then John were all born in London. There may also have been a Tim. Other documentation indicates Denny might have been born in Ireland.

He was definitely in London by the early 1870s and made a name for himself as a barefist fighter. I’ll touch on his boxing career in this article, but most of the piece will be focused on his ‘extracurriculars’.

Alongside three other men, Harrington was put on trial for manslaughter in 1872 following the death of a man named Thomas Callis in a prize fight. Harrington himself was not the opponent, but was charged with being an accessory.

A very curious thing occurred at the inquest for Callis: a young woman called Christiana Callis claimed that Thomas was a cab driver by day and she was his widow. Although she did not live with him, “she was certain he was her husband”. Christiana had taken the money raised by the newspaper Bell’s Life following Thomas’s death, which was intended to pay for his burial.

Another young woman, Jane Callis, was then called as a witness, and she stated that Thomas was a cab driver and she was his widow. She produced a marriage certificate, and said that she had been living with him up until his death last week. He had come home from the fight for fifty quid covered in bruises and told her that they had not reached a conclusion and would be continuing the match on Friday.

Despite being terribly weak, he left home on Friday, and did not return. Christiana then produced her marriage certificate for the coroner. He took a look at both, but could not decide which woman was the lawful wife and had to adjourn the inquest. Harrington was ultimately found not guilty of manslaughter.

In March 1880 he was charged with being drunk and assaulting a police constable at 11pm on Whitechapel High Street. The officer, George Ingram, had come across Harrington out in the street, extremely intoxicated and with his waistcoat off, offering to fight any man who would have him. Harrington then grabbed Ingram and swung him violently around in some sort of dance before tapping him on the chest and saying he’d have a go with him. He was arrested, and sentenced to seven days with hard labour.

A few months later, PC John Tuppen came across Harrington at the more civilised hour of 8.30pm on Cable Street, drunk and making a very great disturbance. Harrington had a basin in his hand and was throwing it up into the air repeatedly, trying to get it to land on Tuppen’s head (go on, laugh, this is one of the funnier ones). Harrington kept missing, and Tuppen grew bored of the game, and took him into custody. Harrington asked the judge if he might look past this incident, just this time, for he’d had a little bit to drink, and he really didn’t have any intention of hurting anybody. He was issued with a five shilling fine or the option of five days jail time if he couldn’t pay.

Harrington was among the ten men arrested for participating in a ‘prize fight in a chapel’ in 1882. You can read more about this event in my blog on Sugar Goodson. Harrington was Goodson’s corner man or second for the fight, and is also credited with training his fellow Whitechapel native – Goodson is referred to as Harrington’s novice in the early part his career.

By March 1883 Harrington had become so well known as a local trouble maker that the East London Observer ran news of his latest activities under the wearied headline of The East End Prize Fighter Again. The article noted that Harrington had, by this point, been prosecuted “a number of times”. On this occasion he was up for another mildly entertaining drunk and disorderly.

Some time after midnight officer Harry Peerless found Harrington drunk (again) on Whitechapel Road (again). Harrington was running around jumping on sailors’ backs. This is definitely one of the funnier ones. He then knocked a sailor down and fell down himself, acting in “such a disgraceful manner” that Peerless had no choice but to take him into custody (again). In front of magistrates, Harrington denied that he had been drunk, and argued that it was all a “get up” by the police and they were, in fact, the drunk ones. No one fell for that argument, strangely enough, and it was another five shilling fine or five days.

One day later, another report appeared in another newspaper, saying that Harrington had been caught waylaying sailors on Wells Street, at about 7.30pm, by another officer. This was becoming something of a habit. A further newspaper referred to the incident occurring on Bell Street, close to a Sailors’ Home. Harrington was supposedly “trying to get a sailor away with him, but the seaman was reluctant to go and resisted him”. It was a month’s hard labour for this – very weird – one.

Okay, so perhaps the obsession with jumping on sailors does sort of make sense, if you think about the fact that Harrington worked as a stevedore or dock hand. There were a lot of sailors about. Perhaps if he’d been a meat porter, he’d have made a habit of leaping onto butchers, we don’t know.

Just two months after getting out of jail, we come across Harrington getting a bit more serious with his criminality. Alongside a John Hayes he was arrested for violently assaulting and mugging a gentleman of his gold pocketwatch, worth £20. The man, Richard Beaumont, had been walking along Dock Street, St George’s East, and about to enter St Paul’s Church, when Hayes approached him and demanded his watch. Harrington grabbed the man from behind, pinioned his arms while Hayes grabbed the watch and both men ran off. Harrington and Hayes got away with it – they were both arrested but Beaumont failed to appear in court and the judge had no option but to dismiss the charges and let the defendants go.

In January 1885, Harrington was charged with stealing a purse containing fifteen shillings from a woman named Edith Austin, a housekeeper. Accompanied by a little girl, Ellen Busher, Edith had been out on Cable Street shopping on Christmas Eve when she decided to pop into the Blakeney Arms pub on Castle Street for a refreshing rum and water. Harrington and another man were in the pub and asked Edith if she wanted another drink, and also asked whether the little girl was hers or not. According to little Ellen, Harrington then pickpocketed Edith’s purse and handed it to his pal. When Edith accused him of theft he denied it, and laughed at her, so she found a constable and had him arrested. The London Daily Chronicle reported that Harrington, aged thirty-five, had at least twenty-seven convictions by this time. Despite his protests of innocence, a jury found him guilty and he received twelve months with hard labour.

Unbelievably, in 1887, Denny Harrington was jumping on sailors’ backs again. You’d think he’d learn. But no. Drunk and disorderly on Wells Street again, jumping on sailors again, and refusing to stop, again. You’d think the courts would have learned too, but Harrington was only fined two shillings sixpence on this occasion.

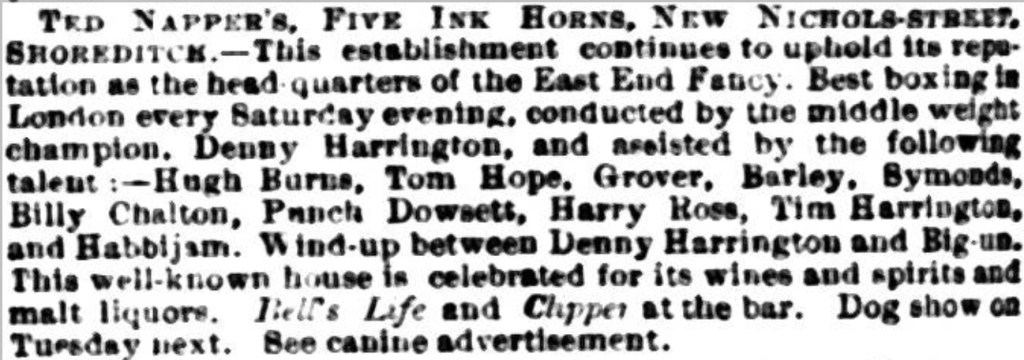

A few weeks later, Denny was held a benefit at the boxers’ headquarters, the Blue Anchor in Shoreditch, to honour his career as a fighter. It’s probably time we talk about that, then:

The “gallant boxer” was best known for his battle with Jem Goode, whom he had defeated after one hour and forty five minutes, and for meeting Alf Greenfield of Birmingham for an hour and twenty.

On the occasion of the benefit, despite the entry price being high, the house was so packed that “the large saloon was literally crammed from floor to ceiling, the craniums of those in the back seats actually touched the plaster”. The night’s boxing programme went on so long that Harrington agreed to cut it short and finish it off the following Monday, closing the night himself by sparring with Jem Kendrick.

Things got a bit less entertaining in relation to sailors in 1888 when Harrington and a friend named Michael Downey were charged with a brutal assault on a William Chatwin, who ended up in the London Hospital. Harrington and Downey had been drinking at a pub by the docks. According to several witnesses, who were all Norwegian mariners and friends of Chatwin, Downey randomly punched Chatwin in the face multiple times, and Chatwin somehow received several broken ribs. However, nobody could confirm that Harrington had anything to do with it, and the judge dismissed him.

At some point, likely in 1888, Harrington took over management of Monday and Saturday evening boxing events at the Red Lion and Spread Eagle on Whitechapel High Street, the same location as many of his drunken late-night run-ins with the law. In 1889 he got drunk on Wells Street, again, and punched another sailor in the face. Is this blog getting a bit repetitive?

Harrington started the 1890s with a bit of sparring, and a bit of hosting boxing events before allegedly seizing, violently assaulting, and stealing money from a man named Matthew Manna in Whitechapel. Despite witnesses identifying Harrington and his friend Ernest Westfall as those who had attacked Manna, Harrington claimed that he had an alibi: he was at a boxing match when this happened, and could fully account for his time. The judge believed him and the case was dismissed.

In June the same year, Harrington – drunk in Whitechapel, as usual – was stopped by a police officer named Albert Barnett, who had seen a large crowd out in the street. Most of them dispersed. One of them did not. Barnett greeted Harrington, who he recognised, with “Denny, what’s up?” then Harrington shoved him in the shoulder, they both fell and engaged in a struggle, before Harrington kicked the officer in the stomach. Harrington claimed he was then “violently used” after being dragged back to the station, with officers giving him a black eye. A twenty shilling fine or 14 days with hard labour for him.

Harrington’s former opponent Alf Greenfield died in a Birmingham lunatic asylum in 1895, prompting several articles in the sporting papers about Greenfield’s heyday. Boxing World and Mirror of Life identified the four top middleweights (men fighting around 11 stone) of the late 1870s as Greenfield, Harrington, Prussian and George Rooke. Prussian had died a couple of years earlier, and Rooke they understood to have gone to America, failed in pugilism, and took work in a factory.

When he wasn’t in trouble with the law, Harrington appears to have spent much of the 1890s going to to the funerals or benefits of his peers. There were a lot of funerals, and a lot of benefits, and it kept him busy and perhaps away from sailors for a while.

The 1901 census lists a 50-year-old Denny Harrington in a common lodging house on Dorset Street, Spitalfields, with dozens of other men, but there is also a 52-year-old Denny Harrington living with his 70-something year old parents Daniel and Mary Harrington down the road at New Martin Street with his much younger brother John. I think the latter is likely to be our man. Denny Harrington does not appear to have ever married or had children.

In 1907 the Sporting Life ran a short article on him titled A Striking Personality. That’s something of an understatement, if ever there was one. It reads:

“The passing of great fighters into obscurity is very vividly recalled by their resurrection in the public prints. Denny Harrington at one period in his life raised great commotion in the ranks of battlers with gloves when scenes at the ring-side were far less peaceful than nowadays. I saw Denny a few nights ago looking hale and hearty and his presence called to mind many exciting episodes in his chequered career.

I believe our first meeting was at the Abbey Arms. Canning Town, when I was going through my baptismal fire as referee. The ring was pitched in the open. Denny fought Bill England, who was intended champion of England but was cut down ingloriously in the flower of his youth. England knocked Harrington down and cried ‘‘That’s one for England.” Harrington knocked England down and shouted “That’s one for Ireland,” and Ireland won.

Later Denny fought Alf Greenfield at the Lambeth Baths, Westminster Bridge-road. There was a serious disturbance, so serious indeed that the shopkeepers closed their shops and put up the shutters. Westminster Bridge-road was in a high state of turmoil and feverish excitement, which did not simmer down until after midnight. Then we find Denny at war with George Rooke (brother to the far-famed pugilist Jack Rooke) at the Surrey Gardens.

Well, Denny lives to tell the story of his fistic exploits, and Saturday next his friends will “rally round him with a bumper” at the Dover Castle, Sutton-street, Commercial-road.”

Denny’s final appearance in the newspapers – I think, anyway – occurred in 1909 and it is very un-funny indeed. His youngest brother John was among four men killed in an accident at St Katherine’s Docks, where Denny had also worked as a stevedore, or dock labourer, for more than two decades.

A lift intended to carry goods – and goods only – up to the top floors of a warehouse was being used by up to 15 men as well, including John Harrington of Whitechapel, 48, Charles Hampton of West Ham, 46, John Homer, 50, Islington, and William Callaway, 26, of Deptford who all died. Three other men were admitted to the London Hospital in a serious condition.

A notice had been displayed advising that men should not use the lift to ascend or descend, but it had been ignored. When the lift reached the seventh floor, a chain broke, and the men plummeted to their deaths. Dennis Harrington told the inquest that despite the visible notice, he and other men had been ordered by their own foreman to use the lift on several previous occasions.

Denny Harrington died in the second week of January, 1911, at the Whitechapel infirmary and was buried at St Patrick’s Catholic Cemetery in Leytonstone, East London. His cause of death was given by the East London Observer as “senile decay” and his age as seventy, although I have him at about sixty. Brothers, nephews and aunts attended his funeral, while old pals from the boxing community carried the coffin. Seventeen floral wreaths, four in the shape of crosses, and two anchors were laid on his grave.

A 1905 article in the Sporting Chronicle recalling Denny Harrington’s glory days provides a better obituary than anything published after his demise. It reads:

“Not tall, but gifted with a herculean frame and indomitable courage, Denny made such short work of any opponent who had the tenacity to face him that soon he earned the distinction of being one of the best heavy-weight boxers in England.

The only man who ever made any sort of a show against this redoubtable East Ender was Jem Goode, elder brother of Chesterfield Goode. They met at a secluded spot down the Thames, and after a fiercely-fought battle, in which they managed to break each other’s nose in one of the rounds, the judge declared the result a draw.

In his fights for the championship with Jem Rooke and “Florrie” Barnett, Harrington disposed of those aspirants for honour inside three rounds, which gives an idea of the hurricane nature of his fighting. Those successes made Harrington a demigod in the salubrious quarter of Ratcliff Highway and its environs, and it was an amusing sight to watch the inhabitants of that classic neighbourhood kow-towing to his majesty the bruiser.

Denny was not at all clever with the gloves. Indeed, there were quite half a dozen middle-weights of his time who could have “put it all over him” in an exhibition spar, but who, had they met him on business intent, within a 24ft ring, would quickly have realised they had no business to be there, for Dennis was the possessor of a punch that meant oblivion, for a time at least, to whomsoever ran up against it.”

Boxers, police officers, or sailors…

Leave a comment