You will not be surprised to learn that eye injuries are common in a sport in which bare fists or fists in large, heavy, gloves make repeated, regular, impact with the face.

Recent research from India with 100 active, adult, amateur male boxers found that 58 men had vision-threatening injuries, such as significant damage to the angle, lens, macula, or peripheral retina. Some of the most common eye abnormalities include traumatic cataracts, or partial displacement of the lens.

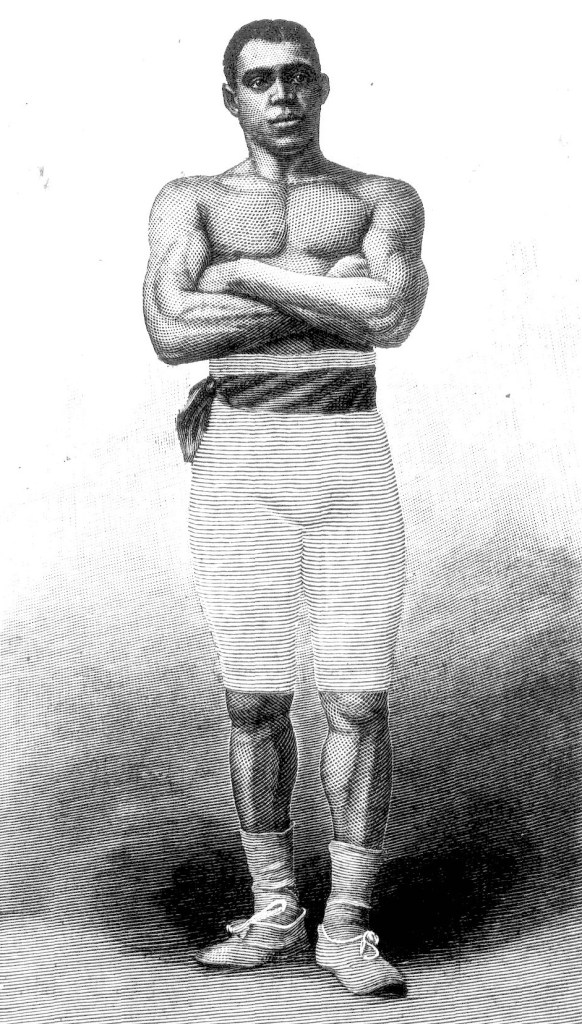

The exact details of Albert Pearce’s injury are not known to me, but the writer of an appeal letter to the Sporting Life indicates that Pearce may have experienced traumatic cataracts – a clouding of the eye’s lens that occurs after an injury – in both eyes. A white or brown discoloration of the lens, often in a rosette type shape, is common, and sight loss can be whole or partial. Traumatic cataracts may occur quickly or develop slowly over time, so it might have been the case for Pearce that the 1894 fight with Ted Rich in Paris was not entirely to blame. The accumulation of three fights with Rich and many years of boxing beforehand may have been.

Read Part I of Albert Pearce’s story, published in November 2024, here

The appeal made by the writer to the Sporting Life saw donations handed in to the newspaper which were then – one would hope – forwarded on to Pearce. The manager of the Reform Chambers, which stood at 541A King’s Road in Fulham (now a handmade bespoke kitchen showroom) donated a sum, while someone known as “Pop” pitched in for 2s 6d apparently, which doesn’t sound like a lot, to be honest.

The following March, Pearce was afforded a benefit at Fulham Town Hall for which vocal, instrumental and athletic entertainments were organised. Advance publicity in the Sporting Life explained Pearce’s situation:

“The once clever boxer has for some long time past been deprived of his sight and in consequence is unable to follow any employment. It has to be hoped that any sportsmen who knew Pearce in his best days will rally round him on this occasion and give that support which the cause fully deserves.”

Past and present champions of the ring were billed to appear, including the former English Heavyweight Champion Jem Smith, Dick Burge (the lightweight champion who later went on to open The Ring).

The Sporting Life’s write-up, under the title of ‘The Blind Boxer’ (feel free to to take that one, pub landlords), noted Pearce’s former prowess as a “smart” runner and walker, and a “proficient” cyclist. It is interesting to see here that his blindness was connected with the match at Newmarket with Ted Rich, not an event in Paris. Pearce was, at this point “blind beyond all hope of recovery even through the instrumentality of the most experienced medical scientist”.

The gathering of music hall and boxing artists was not a success.

“Most of the generous-hearted were… conspicuous by their absence, and in consequence the attendance was most meagre,” the Life’s article concluded.

A Mr Jem Burrows, otherwise known as The Butcher King (fantastic! Hey, Steven Knight, fancy this guy too?) stepped in to cover expenses, ensuring that Pearce did not fall into even greater financial hardship. Despite the poor attendance and lack of funds raised as a result, the line-up of performers itself sounds like a good ‘un: ‘Champion Lady Boxer’ Nora Sullivan gave a most interesting and amusing display of the noble art of self defence against Le Neeve, who had great difficulty in keeping out of Nora’s reach and smart deliveries. The girls were followed by three round exhibitions by multiple men called Jack, Scotch Laddie, Dick Dean and others. Sam Randall, professor of fistic oratory, was an “appreciative” MC.

Pearce stayed connected to the boxing world – his “genial presence” in 1898 at a Lambeth Baths benefit for James ‘Ginger’ Elmer was noted in the press, as was his total blindness by this time.

Another attempt to pull off a successful benefit for Pearce was made the week before Christmas, again at the Fulham Town Hall. The familiar names of Dick Burge, Ginger Elmer, and Scotch Laddie promised to attend.

The Butcher King James Burrows – proprietor of a chain of London shops which, I believe, sold meat – had been planning to return and chair proceedings but a couple of weeks after the Sporting Life had announced the event at the end of November 1898, Burrows dropped dead. The unlucky Pearce’s benefit was postponed as a consequence.

With the exception of occasional fainting fits, Burrows had been in fairly good health, but there had been some indications of heart disease. On Wednesday 21 December he fainted, but recovered. Complaining of heart pains, he lost consciousness on the Thursday. Burrows was dead before a doctor could be summoned.

Describing Albert Pearce as a “well-conducted and plucky exponent of the manly art”, the Sporting Life listed his postponed benefit for 13 February 1899.

Poor, poor, Albert Pearce.

At the end of January 1899, the former cyclist was crossing the road, when a person on a bike crashed into him, and Pearce was knocked to the ground dislocating his shoulder in the process. The benefit was postponed yet again.

Fulham Town Hall was booked for 27 March, with Frank ‘the Coffee Cooler’ Craig and former English Heavyweight Champion Ted Pritchard (who was not far off his early death) leading arrangements, but I’m yet to find any write-up to indicate that it came off. If it had been postponed again, it wouldn’t have surprised me.

A quick line in the Sporting Life that summer seemed to offer a break for Pearce’s run of bad luck:

“We are pleased to learn that Albert Pearce is likely to recover the sight in his right eye.”

Fulham Town Hall was booked again in January 1900, with a Grand Assault at Arms promoted for the benefit of Pearce. A packed programme featured an array of champions from the late 1890s, club swinging by Tom Burrows (“Champion of the World”) and a gymnastics display by members of the popular German Gymnasium – one of them managing to break the bar installed for them to swing off. It was a capital show, backed and MCd by Mr Bettinson of the National Sporting Club, but attendance was yet again poor.

There’s little to be found on Pearce’s 1901 benefit, but it appears another one took place: “Jack Bird’s midgets, four in number, will box for the benefit of Albert Pearce, the black,” according to the Sporting Life.

Pearce’s name slowly started to disappear as the new century got going. He wrote into the paper occasionally, in the way that many athletes and those in sporting circles did at the time, using it as a social media messaging service to request others to contact him. His messages give the address of 3 Bridge Road, Hammersmith, and later 14 Bridge Road.

When the Life heard in 1899 that Pearce might recover his right eye sight, they appear to have heard wrong. In 1903 a collection, or subscription, was started for Pearce to enable him to go to Germany to consult with a Professor Pagonstecker of Wiesbaden, a celebrated oculist.

But in 1906 he was still blind, and still having to beg for support. The Sporting Life reported that he had recently survived a “very dangerous illness” and was “in great want of assistance, and would be deeply grateful of any contributions, no matter how small”. In this piece, the scene of the match in which he met with the fateful accident is again given as Newmarket.

“He is well remembered as a game, resolute, boxer, who never shirked the responsibilities of an engagement with the best and strongest”. Albert, I imagine, probably wished he had.

READ PART III OF ALBERT’S STORY

Nb. Part III reads a bit like a conclusion, but research into Albert is ongoing and new findings have appeared (particularly about his early sporting career) since writing it. I’ll be saving these findings and more for a book.

Leave a comment