The number of eyes in Stephen Graham’s head probably wasn’t the first thing you noticed about him when Empire magazine published exclusive first-look photos from the forthcoming TV series A Thousand Blows. This is completely understandable. But take another quick look, or a longer one if you like, and observe: he has the standard quantity (two).

In Steven Knight’s new drama, Graham plays 1880s boxer Henry ‘Sugar’ Goodson and like others in the show who carry the names of real people from the period – Treacle Goodson, Punch Lewis, Hezekiah Moscow and Alec Munroe among them – his character is very much an ‘inspired by’ or ‘based on’ depiction. A Thousand Blows is not a documentary: the characters and storylines are the creation of a wonderful team of writers, and it is only in little snippets here and there that they cross paths with reality.

As such, please be aware that you can read this blog, or any of my previous pieces on Moscow or Munroe, without getting any spoilers about the show. As A Thousand Blows’ boxing historian or historical consultant, I am contractually obliged to not give anything away (and even if I wasn’t, I wouldn’t, because that would be a terrible thing to do). This article sticks to the truth, and delves into Henry’s real life and times, including the fact that, for much of his life, he seems to have only possessed one eye.

Sugar Goodson is certainly not alone in the Victorian period as a boxer with only half his vision. It was a subject which interested the readers of Victorian and Edwardian boxing magazines: several articles were published in the late 1800s and early 1900s on the subject of the era’s cyclopian order of pugilists.

In 1897, a piece on mono-visioned boxers noted that boxer Jem Belcher lost one of his playing racquets. Bill Hayes and John ‘Bos’ Tyler are mentioned, and Dunbar from Wales. Dunbar lost his in an accident with a gun, I believe. Bill Gibbs, one of Alf Ball’s boxers, just had the one “but it never affected his boxing” (Boxing World, 1898). Jack Davenport had two eyes, but after one of his many stints in prison, found himself with ‘a cast’ over one of them. Jimmy Connolly, explained Boxing in 1910, had a glass eye, over which the lid didn’t close. Passed out in a pub one night, he avoided becoming the victim of pickpockets, who had approached thinking he was asleep, only to spot his false eye open and staring into their souls while the real one rested. Most of the boxers who had one eye lost the other one because they were punched very hard and very regularly in it.

I cannot find a single article or other piece of evidence which explains how or when Sugar Goodson lost his eye, I only know that he probably did. There is an anecdote that was published in 1904 and suggests that at the time of his notorious prize fight in a chapel in 1882 against a man almost three decades older than himself, Goodson’s eye had been closed for some “ten or a dozen years”, thus placing its disappearance around 1871 when he was in his mid teens. Anecdotes in articles published many decades later are not necessarily reliable, and it seems remarkably strange that in write-ups of Goodson’s early boxing years, there appears to have been no mention of his only having the one. We know it wasn’t an unusual state of affairs during the time, but possessing only one eye still seems like the sort of detail that the era’s detail-orientated boxing reporters might have jotted down, as they did with height, weight, or skin colour.

Let’s go back a bit, and we’ll return to the eye, or eyes, later.

This article is inspired by years’ of research produced by one of Goodson’s great great granddaughters and published after she’d read it. I have not written an exhaustive account of Goodson’s entire life and career, but will be focusing largely on the year 1882. There will, hopefully, be more to come later.

Henry Goodson was born at Seven Stars Yard off Brick Lane on the 19th February 1856, making him a contemporary of Jack Wannop (born late 1854) and the real Alec Munroe (1855), and just a few years older than Hezekiah Moscow. At three weeks old he was baptised at St Mary’s, Spital Square. Goodson’s father Edward was a master carman (the driver of a horse-drawn vehicle) with a haulage business, and with wife Sarah they had 13 children. When Edward senior died in 1877, the business was taken over by the eldest son, Edward, and he employed the rest: Benjamin, Thomas, Joseph, Henry and John.

Henry married Ann in 1876 and approximately 10 months later, their first son James was born, then two more sons, Joseph and Edward, arrived over the next couple of years. It’s in the late 1870s that Goodson, who had been training with boxer Denny Harrington, starts to appear in the boxing reports – always as Sugar – sparring in the East End’s finest boxing pubs, including the Mile End Gate Tavern. The Sportsman offered a brief description of his appearance – “strongly built” – in January 1880, but offered no observations on his eyes.

In January 1881 Sugar was on the bill at the Five Inkhorns, Shoreditch, to box Harrington but then disappeared entirely from listings for some eight months. The reason can be found on the 1881 census: Goodson was separated from his young family living on Brick Lane, and resident instead at the Deptford District smallpox hospital in New Cross, south east London. When the 25 year old carman was admitted and when he was discharged, I’m not sure, but he was certainly back on home turf by August, in time to take on the management of a new boxing saloon, and to father another son. Arthur Goodson was born on Brick Lane in May 1882.

Smallpox can damage the eyes. The virus which causes smallpox can cause “eyelid and conjunctival infection, corneal ulceration, disciform keratitis, iritis, optic neuritis, and blindness”, although recent research suggests that only 5-9% of (modern day) patients with smallpox will experience these ocular complications. In the less-sanitary and medically-knowledgeable 1880s, perhaps this was higher. Smallpox could explain why Sugar only had one eye but if that’s the case, why did the writer in 1904 seem sure it had already gone somewhere long before? A tip from one of Goodson’s descendants is very helpful here: perhaps the journalist who wrote that the eye had gone somewhere ten or a dozen years prior to 1882 actually meant to write ten or a dozen months, ie. in 1881.

Two years before his untimely death, well known MC Punch Lewis (William Caddell Lewis) opened a ‘commodious’ boxing saloon at the Blue Coat Boy at 32 Dorset Street – opposite Spitalfields Church – in August 1881 to mark the start of the boxing season. He placed Sugar, and his brother Tom, in charge. There’s little surviving to say what it looked like but newspapers’ reports suggest the room to have been “grand” (as grand as it could be, in an East End pub, on a street which became known as ‘the worst in London’), with a “capital stage” erected in the centre, giving “fine views from all angles”, and it was “much wanted” in the area. You’ll see next year that the creative minds behind A Thousand Blows have done a stunning job at recreating it, with little to go on.

Alec Munroe and Hezekiah Moscow (billed as Ching Gook, and described by the Sporting Life at this time as – please excuse the phrases – “the Chinaman” or the “swarthy Celestial”) were among exhibition boxers sparring there from the start.

We can see from reports in the Sporting Life that Sugar was fighting fit from August, sparring with Tom and Denny Harrington at the Blue Coat Boy and others elsewhere, and advertised in the Sporting Life as open to sparring with all-comers. There is not, among any reports, any mention of him heading off to hospital with two eyes and returning with one.

On the 1st February 1882 Sugar Goodson, aged 26, and Jack Hicks – almost three decades Goodson’s senior – were matched to fight for a silver cup said to be valued at £100. The veteran had failed to get a match on with Hugh Burns to determine who was the better middleweight champion – Burns had supposedly turned up 2 and a half minutes too late to post his deposit and had to forfeit. So Hicks threw open his challenge for anyone’s acceptance, and in stepped Sugar. It was agreed that the fight should come off within the next eight weeks, under Queensberry Rules and in a meeting at the Sporting Life’s offices the parties settled on March 27th. Sugar had continued to spar at the Blue Coat Boy, then gone into active training in early March with Denny Harrington at the Wakes Arms Inn, Epping.

Hicks was born in Mile End in 1827 and had his first fight five years before Sugar Goodson debuted on earth. That 90-round barefist match lasted just shy of three hours.

Hicks stood at 5ft 5 and a half, just a smidge shorter than Goodson’s 5ft 5 and ¾, and weighed in at 10st 2, with Goodson at 11 stone. These facts and figures come from the Sporting Life’s match write-up. Again, among brief biographical and physical information, there is no note of any sort on any kind of facial impairment Goodson may have recently, or less recently, experienced. It just all seems a bit odd.

In 1882, Sugar was still a relative novice, having engaged in three-round spars and exhibitions over the previous half-decade but with only two relatively short professional fights under his belt, but was considered a good match for the much more experienced Hicks.

An aside: despite his compact size (Mr Graham was an excellent casting decision!), we know Goodson to have later competed on occasion in heavyweight competitions – English Champion Jem Smith beat him and Jack Wannop, in 1885, for example. At around 5ft 8 and 13 stone, Smith and Wannop were among the largest men with any boxing ability that London had to offer.

While announced well in advance in the much-read Sporting Life, openly advertised, and much anticipated, as prize fights of this sort were still very much illicit activities, the event’s venue had been kept a closely guarded secret. But as the Life’s reporter explained it:

“As is generally the case with matches of this kind, a friend was ‘let in the know’; that friend had a friend who had many friends, and consequently a vast number of people assembled at the venue selected.”

The venue was a deconsecrated chapel off Tavistock Square, a piece of information that had been liberally disseminated in the East End. The Pall Mall Gazette later reported that Epping Forest had been originally in mind as a place most likely to be free of official intrusion, but some bold spirit had hit upon the idea that central London, directly under the noses of the police, might be the safest space. According to some reports, the keys to St Andrew’s Hall were supposedly acquired under the false pretense that a party of gentlemen wished to hold an assault-at-arms (boxing and other military exercises, held without the excitement of a cash purse) for a benevolent purpose, while others suggest that the keys had been given to a party who wished to inspect the rooms as they were looking to form a new club which needed a space.

The chapel had gone by a variety of names over the decades and in the early 1880s gained something of a nefarious reputation due to activities on the premises even more unholy than prize-fighting: resident Archdeacon Charles Gordon Cumming Dunbar (no relation, I believe, to the previously-mentioned one-eyed boxer Dunbar) had allegedly engaged in so many extramarital affairs on site that his wife tried to divorce him. This article from the UCL Bloomsbury project gives further detail.

Two exhibition spars went off uninterrupted, then Hicks and Goodson – both in short drawers – made their way to the 24ft ring erected in the centre of the room, the posts driven into the earth where tessellated concrete flooring had been dug up, and a carpet stretched between them.

Denny Harrington and Punch Lewis acted as Sugar’s seconds, while Hicks was accompanied by Dutch Sam and original opponent Hugh Burns. The referee read out the rules and reminded the gathered crowd that should they become too noisy, he would stop the contest. So far, so respectable.

The Sporting Life’s reporter remarked that both men appeared wonderfully well as they toed the scratch. Goodson led off and planted a left then crossed his opponent on the jaw. Some desperate two handed work followed from both men followed by a good rally up against the ropes. Goodson took it to Hicks’ body before the veteran planted a strong right hand on his opponent’s jaw. The pair hammered away as round one drew to a close. Some severe work in round two left Goodson groggy, and while Hicks seemed far from fresh himself, he appeared to be on top. As round two closed, the audience cheered, and were quickly suppressed by the ref.

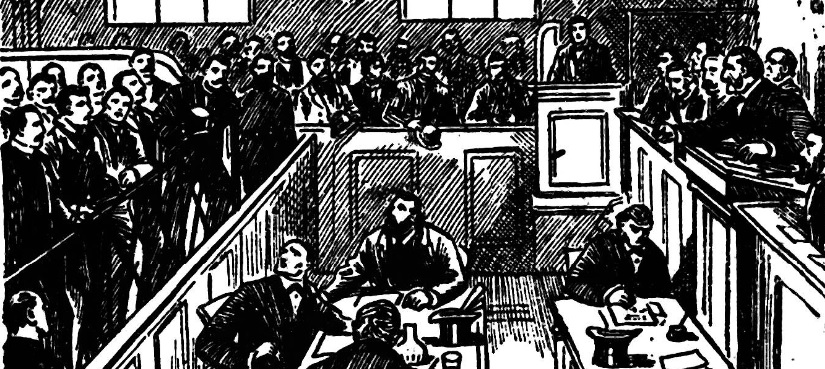

Hicks led off round three, landing blows to Goodson’s belly, ribs and face before Goodson crossed his man on the cheek. At close quarters, he “finished his man off”, Hicks falling to the canvas. Just as they were about to complete the round… all hell broke loose. The fight was stopped, the police inside the hall sprung into action, and those who had appeared outside were attacked by something of a mob who had gathered to hear, if not see, the action inside. Dozens of men sprinted out of the hall into the night. Ten, including Sugar Goodson, were handcuffed and dragged off to the station.

This fight and the subsequent trial of some of its participants attracted such a huge amount of press attention, by virtue of the novelty of its location, among other factors, and it is quite a task to discern fact from fiction and weigh up statements from defendants, witnesses and police. For a boxing match which lasted all of eight and a half minutes, it caused quite a sensation in 1882 and continued to be discussed for decades after.

Typically, the reminisces of older gents writing colourful copy in papers such as the Illustrated Police News many potentially-booze-addled years after the fact might not be my go-to source for accuracy. But the author – and I am not sure who they were – of a three-part 1904 Great Glove Fights story on the Prize Fight in the Chapel tells a fantastic story, in decent detail.

He was at the scene at the time, appears to have known many of the parties involved, and specifically mentions the poor quality of the media coverage in 1882. Much of the original coverage appears to have been wire copy distributed to dozens of regional and national newspapers, and that means that falsehoods or mistakes that might have been included were printed everywhere.

The Police News writer was convinced that the match, which he describes as “the most curious” of chapters in the history of prize fighting, was a set up designed to fleece, or “tap the pockets” of unwary paying spectators, before being broken up early. The admission charge was £1 or £2 (£100-200 in today’s money, according to the Bank of England’s inflation calendar), he says, and the entire thing simply seemed deeply suspicious from the off. His back story was thus: the writer enjoyed a game of billiards and had ventured to the large rooms above Blackfriars District Station where a billiards club was being managed by a Mr William Elton Fuller – a former athlete – and John Garrett Elliott, the latter being the man who was to fraudulently acquire the keys to the chapel at Tavistock Place. Elliott thrust into the writer’s hand a card which was inscribed “Monday, March 27, Gower Street Station, one o’clock”, rendering him in the know and “determined to see the fun”.

While both Hicks and Goodson had allegedly spent several weeks training ahead of the fight, neither was in particularly good shape, according to the Police News writer, who had met some of the “short-haired fraternity” at Gower Street before being taken to the chapel. “There was certainly room for improvement in the condition of both, especially Goodson,” he’d observed, questioning whether either pugilist was taking this affair seriously. Garrett Elliott had acted as doorman and there were recognisably, to the writer, a number of plain clothes police officers dotted around. Whether Elliott knew of their presence or not, the writer is not sure, but he thinks he may well have done: the Police News fellow couldn’t imagine any of the officers (that he’d immediately recognised) to have made their way inside having paid a hefty £1 or £2. Among the audience of around 250 people, he positioned himself close to the door, ready to make a swift exit if, or when, required.

What happened next as described by the police and prosecutors in court and by the national and regional press differs from the Police News writer’s recollection and explanation of things. An East London News report from Henry Goodson’s pre-trial hearing at Bow Street Police Court – he was charged with being the principal engaged in a prize fight, while nine other men were prosecuted for aiding and abetting – describes the evidence given by Detective Scandrett, who had been at the hall in plain clothes:

“The prisoner Goodson and another man came into the ring… they fought and while they did so, the two seconds for each man stood in the ring. The two combatants had gloves on similar to those used by a wicket keeper. In the first round Goodson struck the other man in the face, and he fell up against one of the wooden staves and broke it. Hicks fell down and when he got up there were streaks of blood on his back. They fought again, and hit each other very hard, Hicks being again knocked down. While he was down, Goodson kicked him. The lookers-on got so excited – some of them had sticks – and one of them struck Goodson.”

At this point, an incensed Sugar yelled out from the dock that he had three little sons at home and if any of them said anything like that (ie. if they were lying, generally, or perhaps specifically making false claims about their father kicking a man when he was down) “he hoped they would die”. He continued to yell excitedly that “he couldn’t stand it, and that it would be better to be chucked in the river than to listen to such lies”.

Having been forcefully told to shut it, I expect, the detective continued giving evidence, mentioning the vigorous nature of the fighting, the blood visible on Sugar’s face, and claiming he’d seen betting going on at the chapel’s Communion table. Under cross examination he admitted that the gloves may have been slightly padded, but they were not the “normal” sort that had been used in the warm-up sparring before the main event, and he reiterated that Goodson definitely kicked Hicks in the thigh, hard, while the older man was on the ground.

Police Constable Cooper backed him up on the “very thin” gloves, before a third witness, a policeman called Fancy William (sure, why not!) described the scene outside the chapel as he and his colleagues broke up the fight: some 100 to 200 men were gathered around the door demanding the release of the arrested men, and one of them kicked an officer in the head.

Speaking of the arrested men, it should be mentioned that neither Garrett Elliott or Jack Hicks had been detained, nor had several other key actors in the fight, despite the fact – according to the recollections of the Police News reporter in 1904 – there were loads of police in and outside the room and just one door to enter and exit. Just a tiny bit, suspicious, right?

Before the defendants were committed for trial, Charles Bedford, the man who had read out the Queensberry Rules before the start of the match, had a chance to defend himself, and explained that he had attended the affair as a reporter (he worked for the Sporting Life) but had been asked to stand in as referee because of the fairness in which he had conducted previous Queensberry Rules fights. He told Hicks and Goodson that the rules must be abided by and anyone who slipped up would be disqualified. Bedford maintained that no kicking or striking on the ropes in a helpless state had occurred and both men were engaged honorably in a fair fight. He also maintained that the gloves used were the same as in the earlier sparring: normal, large, padded, Rules-compliant boxing gloves.

Bedford had not actually been arrested at the match alongside his fellow defendants, but had voluntarily turned himself in as a protest against the gross perjury committed by the police. He was taking a stand in the name of public justice.

In a second examination at Bow Street, several other officers came forward to give evidence. Inspector Arscott, who had apprehended Sugar’s second, Harrington, believed the gloves used to have been unpadded, or very lightly padded, and that the first and second rounds were longer than the regulated three minutes. The witnesses also described the items brought to the ring by the fighters’ seconds – ice, water, brandy and sponges – as being those associated with something far more brutal than a sporty bit of friendly sparring.

One of the prosecutors did make a fairly good point: he argued that the high door charge of a guinea (more than £1, or £100 in today’s money) would have been absurd for “an ordinary sparring match”. This ticket price alone was an indication that the combatants were to engage in a prize fight where they would inflict real injury on each other ie. the gory good shit that certain types of men would pay a premium to see.

Mr Hopwood, a butcher from Cable Street, Whitechapel, in the heart of the East End, backed up the accused by stating the gloves they wore were no different to those covering the hands of the men sparring earlier in the night. He saw no striking with sticks and no kicking. He’d only paid half a sovereign for his ticket, by the way.

Ahead of conclusions in the trial, Mr Keith Frith, representing the defendants, observed that up until the time of this gloved contest, “there had been no judicial decision that glove contests for endurance were illegal” and since Goodson did not kick his opponent – he maintained this was a fiction generated by the police as an excuse to halt the fight – he hadn’t, technically, broken the law. Another lawyer, Mr Besley, urged the point that in countries where boxing isn’t taught, men are much more likely to do harm to each other with their feet and knives. So boxing is quite good, on balance, isn’t it?

Through court transcripts conferred by the press, it is difficult to draw a conclusion on who was right and who was wrong and what actually happened on the night in question, but it is a fascinating exercise to have completed and one that could have run to may more thousands of words here.

Hicks was a 30-something year veteran of bare knuckle fights and an unlikely candidate for a gloved-up Queensberry rules match, but by 1882, in his mid-50s, maybe he just fancied a change. The strange set-up for the event itself, where he messed around his original opponent, got Goodson on board, and then had his opponent as a second – and the fact Hicks wasn’t arrested – is definitely a bit odd.

I was inclined to believe that the combatants may actually, in line with police evidence, have been wearing some form of non-compliant lightly-padded skin gloves, they being both commonly used and a compromise between bare fist and fully padded. But would they have been daft enough to do so at a central London venue in front of a large-ish crowd? Or were Bedford and his fellow defendants telling the truth when they claimed that normal gloves were used, and they’d been mysteriously disappeared by the police? And if Goodson had really kicked Hicks while he was on the ground, why didn’t the Sporting Life’s brief blow by blow account of the match, published straight afterward, mention this? Or perhaps it didn’t mention it because it might have been filed by the referee himself, Sporting Life writer Charles Bedford?

It seems to me – but I’m still not entirely certain – that the Prize Fight in the Chapel was a stitch-up on two fronts: Garrett Elliott and his partners were out to make some cash by charging a lot of money to a fight they knew would get closed and they could escape from without dishing out prize money to the winner. And the esteemed officers of the law were determined to show that they were cracking down on prize fighting.

Whether the two parties were working together, and what Sugar Goodson’s involvement in it all may have been, isn’t clear, but I can’t see any evidence that he was anything other than the fall-guy.

Backed by friendly newspapers keen to amplify outrageous events and sell more copies, the police force’s stoppage of a fair fight under Queensberry Rules, in a room that was no longer used for religious purposes and may not even have been consecrated in the first place, became a violent bust up of a blood splattered, uncivilised, brawl in a house of God. Perhaps.

In their coverage of events, published on 29 March 1882, the upmarket Standard gave their view at length. Some extracts:

“The practice of holding Prize Fights under the disguise of boxing matches has become more and more common of late, the pugilists using, as in this instance, not the well-padded gloves of the gymnasium, but such as form no protection at all, except for the purposes of the Police-court, in enabling a witness to swear without actual perjury that the men ‘had the gloves on’.

“The persons concerned in the Tavistock Chapel Prize Fight belong entirely to the dregs of the population, and happily no one with any pretence to respectability countenanced the disgraceful scene.”

“The attractions which physical sufferings and endurance have for uncultivated minds, and the fascination which gambling exercises over ill-trained persons, will probably make it impossible absolutely to abolish Prize Fights, but Police vigilance can, if properly exercised, prevent such exhibitions from being obtruded on the public. The Tavistock-place scandal is so exceptionally disgraceful that there is little necessity for guarding against the repetition of its sacrilegious details…

“It is high time to make some notable examples out of the delinquents.”

On the 21st May 1882, The People and other publications published on the final day of court. This story had run and run for days. The Assistant-Judge in the case stated that he was convinced that, despite numerous police officers claiming that the fists of Hicks and Goodson were clad in light wicket keepers’ gloves, he was convinced that ordinary (large) boxing gloves had been worn. Further, he was convinced by the evidence that Goodson had not kicked Hicks at all.

He was not, however, convinced that this was not a Prize Fight that would have continued to “the point of exhaustion”. It was of “illegal character” and “fraught with all the mischief and evils of a prize fight”. He was definitely pissed off about the use of a chapel, given it still had all its “divine fittings” but was aware that it had been advertised for use as a gymnasium, and had not been used as a place of worship for some time.

Goodson and some of the other men accused of aiding and abetting were let off with a caution not to engage in similar proceedings again. The chap who kicked the police officer outside got a £5 fine. The judge, Mr Poland, said that a watch would be kept on such contests in future.

Alongside The People’s report was inserted a letter from the Archdeacon Dunbar – he of scandalous repute – seeking to correct recent reports that St Andrew’s Hall was actually a hall, not a church. It was definitely a church, he said, not a hall, and he’ll be reopening it for worship soon (presumably without the late-night womanising).

According to the UCL Bloomsbury Project, Dunbar’s license to preach had been revoked by the Bishop of London in 1880, and he was prohibited from preaching. The Foundling Hospital’s trustees took legal action to stop him using the chapel and were successful, and in 1884 it was reopened as an additional premises for a furniture business. In 1885 it was badly damaged in a fire. After a few years as a cycling school, the notorious chapel that sort of, kind of, wasn’t, was demolished.

Sugar Goodson most certainly did not keep out of such contests in future. There is plenty more to write on his life, family, and career from 1882 onward and I hope to do so in a further blog. Very much aware of the length of this one, we’ll skip forward a bit for now.

In 1901, Jack Hicks wrote to Boxing World and Mirror of Life in response to their article on “old pugilists” and offered to challenge any man over the age of 70. He does not appear to have had any takers.

In July 1904 the Illustrated Police Gazette News published their “History of the So-Called Prize Fight in a Chapel Which Led to Numerous Arrests” and two months later Jack Hicks, died at the aged 78. Sugar Goodson, his final opponent, attended the funeral at Woodgrange Cemetery. Some 30 years later, one of Hicks’ trainees, 1890 English Middleweight Champion Toff Wall remembered him in an article for The People. Jack Hicks always wore a top hat, he said, even when “flapping a towel or rubbing me down. Some people, indeed, said that he slept in it”.

The Prize Fight in the Chapel was written about for years to come. More often than not, when Sugar Goodson’s name appeared in a newspaper in connection to his pugilistic activities or those of his son, that 1882 event was noted in brackets somewhere in the story.

In 1911 – possibly inspired by the longevity of Jack Hicks’ career, Sugar Goodson entered the ring once more against a man of a similar vintage, Jack Collinson. At The Ring, Blackfriars, the “two men of 60 years old” (Goodson was actually about 56) did battle, the bout being stopped in round two when Collinson did damage to Goodson’s left eye. According to Boxing, Sugar offered up £25 to Collinson for another go. “Those gallus old-timers! Can’t keep them out of the game. Feel like little chicks when they see the gloves flying, and just itch to get going themselves,” the newspaper said. The itch, or for the love of it: a far nobler reason for taking the risk in your 50s than Mike Tyson’s forthcoming multi million pound payday.

Sugar Goodson died in Chingford on the 27 August 1917. With so many of his peers long-deceased, and in the midst of war, I thought there may have been little to find on his departure in the newspapers currently at my disposal. But a columnist for the Evening Dispatch, published a short obituary two weeks later, almost entirely about the prize fight in the chapel, and The Sportsman obliged too, with a column on “The Death of a Veteran”:

“The rumour which was abroad towards the end of last week that a once well-known boxer had passed away was actually based on fact. It referred to Henry (‘Sugar’) Goodson, of Mile End, who flourished in the early ‘eighties as a middleweight. Goodson was contemporary with Denny Harrington, Greenfield, Jack Hicks, and other well-known men, and though a useful cut-and-come-again fellow, he never soared to very great heights.

“He had a defect to the eyes, but I do not think he was quite blind of the right: still, I know there was something the matter with it.”

“He was a good boxer, if not particularly clever, was Sugar Goodson, and a good fellow, if a rough diamond.”

A good boxer, with two eyes, apparently – even if one was a bit dodgy.

And now a name that will be immortalised by one of our country’s greatest actors.

Leave a comment