This is the second chapter of Ching Hook / Ching Ghook / Hezekiah Moscow’s story. You can read the first part (which includes information about why I’m researching him and what on earth all the name variations are about) here.

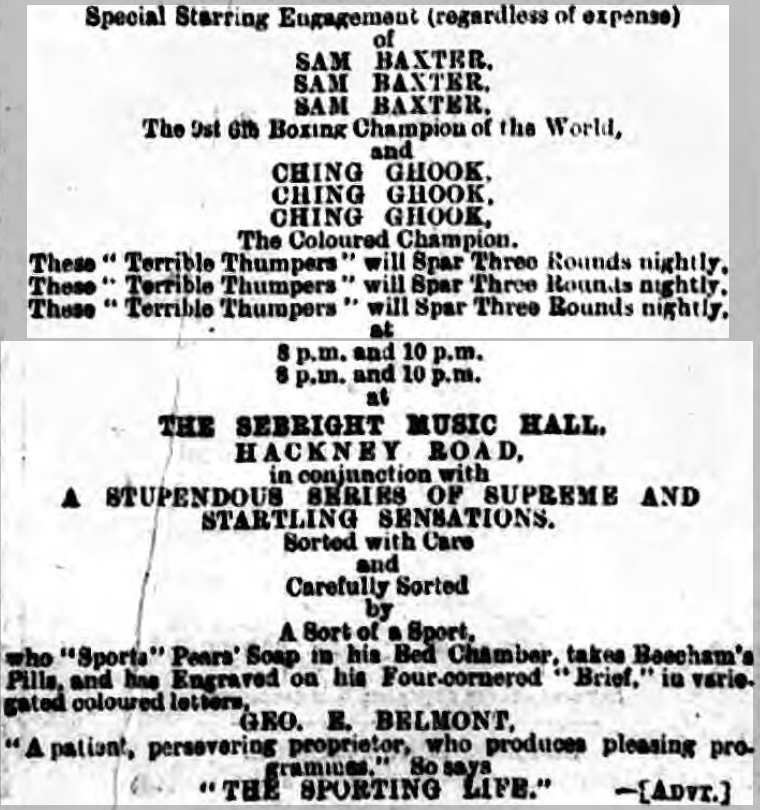

The year 1888 started well for Ching Hook, with a week-long residency at the Sebright Music Hall, sparring twice a night every night at 8pm and 10pm with Sam Baxter.

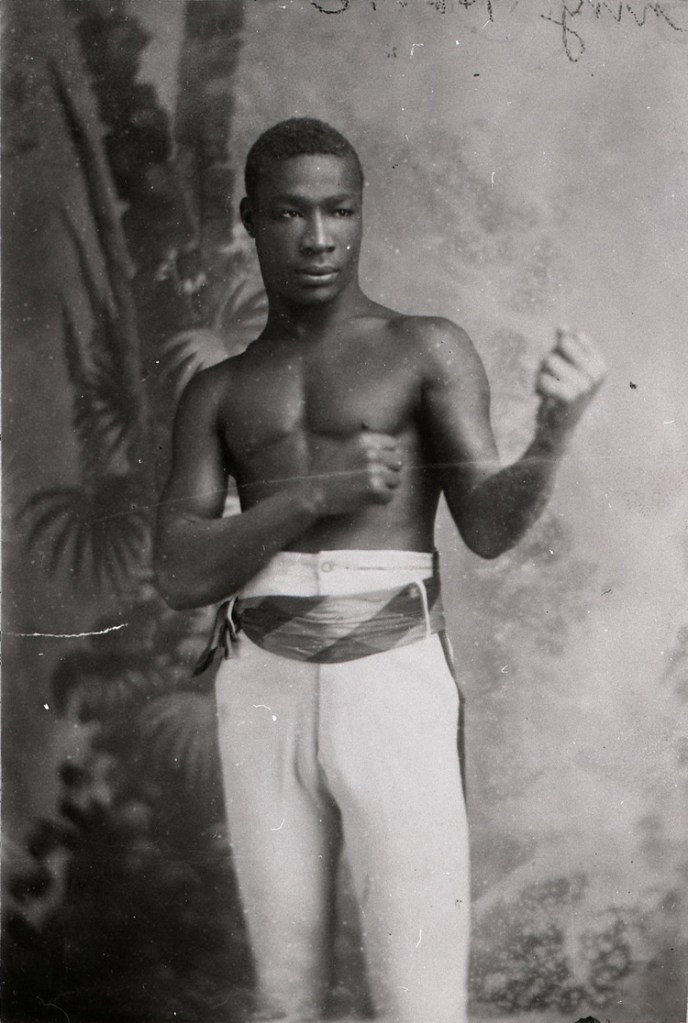

At 5ft 7.5 and 21 years old, it was said by The Sporting Life that “no boxer of Baxter’s age and inches had achieved so much”. Hook was billed by the Sebright’s promoter, George Belmont, as the black “champion of the world”. This was complete nonsense – Canadian George Godfrey held the official World Colored Heavyweight Championship title at the time in America and a few months later was beaten for it by the Australian Peter Jackson – but it was a nice bit of PR from Belmont, a king of copywriting. The crowd’s enthusiasm was boundless.

“The house rose en masse when the men appeared on stage, and before they were allowed to place themselves into position, had to bow their acknowledgements over and over again. The place was crammed to suffocation, and money was unwillingly refused [the place was sold out] at 7 o’clock…”

“Sam is a mild inoffensive youth, and wears the sort of harmless kind of look that usually points a man out for a licking when somebody has got to be walloped… Ching Ghook is equally deserving of praise… possibly a better matched pair could not be found to illustrate the art of boxing, as each man is in the front rank of his profession.”

The Sporting Life also enthusiastically noted that “both were faultlessly attired, and their sleeveless jerseys showed their biceps and triceps to perfection” and the men’s performance caused “much merriment, particularly amongst the fairer sex”. Baxter was said by the newspaper to have the advantage in height and reach, although just a month later we find him in a 9 stone 6lb competition and Hook fighting against men at 10 stone 2.

Alongside the boys on the bill were singers Tom Gannon and the Sisters Briggs; Charles Raymond “the one legged phenomenon”; the singer and comedian Smythe Cronin; Charles Diamond, harpist and dancer; and Harry Lynn and his “clever daughters” in a “well-written sketch”. After the boxing, the programme wound up with Tom Murray the whistling wonder, and Professor Baker’s “Theatre of Arts”, whatever that may be.

Rather amusing praise for the Sebright’s George E. Belmont, appeared in the London and Provincial Entr’acte on 7th January:

Later in January and into February we find Hook seconding young fighters or acting as MC at exhibition bouts at the Old Mile End Gate Tavern and the Queen Adelaide in Whitechapel, before taking a benefit at the Blue Anchor in Shoreditch. The latter event saw an unnamed trainee of Hook vs Jimmy Earle in a bout that “afforded continual merriment, both striking some very funny attitudes and giving away each other’s heads to be tapped” (The Sporting Life, Wednesday 15 February 1888). A chap called Clarence Holt also encouraged his 8-year-old dwarf nephews to get in the ring.

In August 1888 Hook was handed the keys to the City of Norwich pub on Wentworth Street, Whitechapel. The “well ventilated” and spacious gym, with its 13 foot boxing ring, was now under Hook’s management and public sparring took place every Saturday and Monday night. Granted the honorary boxing title of Professor by the end of 1888, we also find Hook teaching every Tuesday night at the Watford Boxing Club.

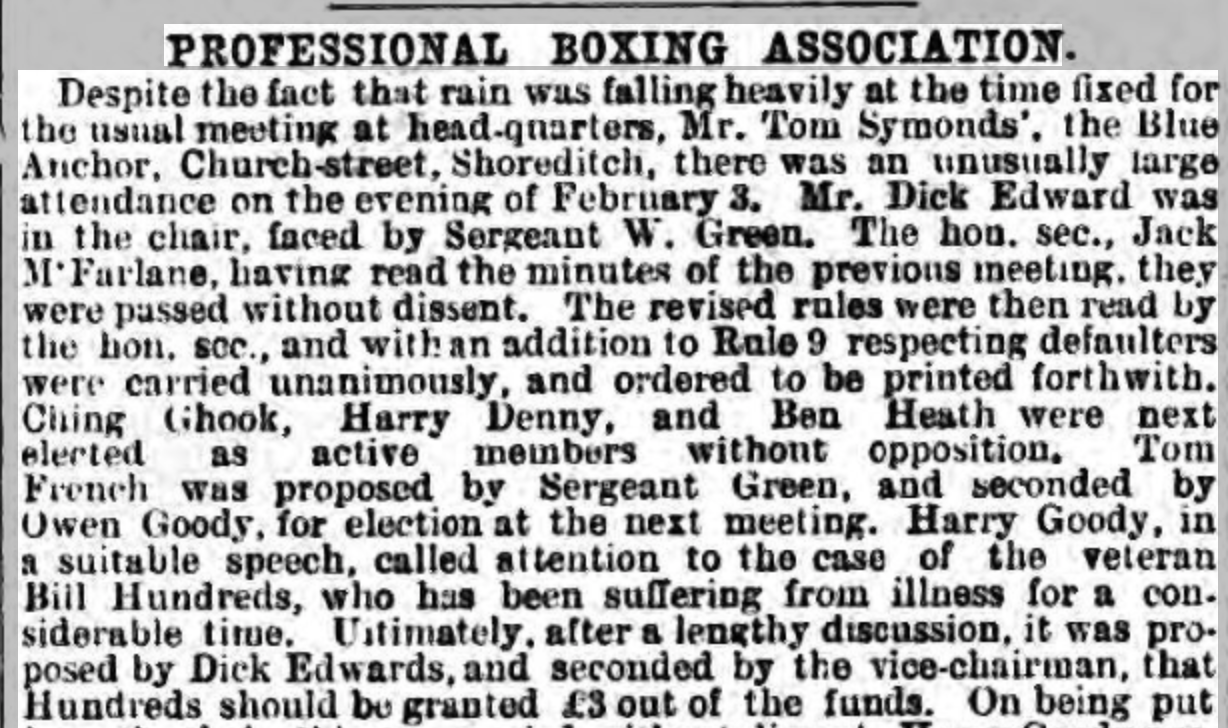

He was back at Belmont’s Sebright to kick off ’89 with a week of exhibition boxing against another black “champion”, Jack Watson, and on the 3rd of February that year Hook was elected, unanimously, by members of the Professional Boxing Association to become an active and voting member. The same week, Watson and Hook joined the weekly changing company of sketch artists, singers and performing animals at the Royal Albert Music Hall, Canning Town.

At the end of August 1889, Hook took over management of the boxing saloon attached to the Walnut Tree pub on Bull Lane, Stepney. A Sporting Life article titled CHING GHOOK’S OPENING NIGHT described the place as “crowded to excess” for his tournament open to men under 8 stone 4lb. Across 1889 a scattering of references to Hook not fighting at quite his best begin to appear but are countered with regular praise for his fighting skills, oratory abilities and ability to entertain with comedic talent.

On Saturday 25 January 1890 a 16-year-old printer named Arthur Knight collapsed and died in the ring at the Exmouth Arms, Clerkenwell, at a night of exhibition boxing run by Hook, as “master of ceremonies”. An uncle of Knight’s stated at the inquest a week later, that the lad was an epileptic and “not strong” yet he was a regular attendee at the Exmouth Arms boxing club where he had trained without a problem.

After about a minute in the first round of light sparring, someone called time. Knight was “rushed” to his corner by Hook, where the teenager fainted. Every effort to revive him was sought but by the time a doctor arrived, Knight was dead.

Dr Eber Chambers, performing the post-mortem, found no injuries at all upon Knight’s body but death was said to have been caused by “compression on the brain” leading to a rupture of blood vessels, “caused by a time when the young man was excited, and the heart’s action was accelerated by boxing”. Edward Barry, his opponent, was also Knight’s housemate, they both wore gloves, and neither had delivered a hard blow in a bout that was only meant to show form. The Coroner observed that the rupture may have been caused by any sort of excitement, boxing-related or not, and a jury cleared Barry, giving Knight’s death as “natural causes”. Two days after the inquest, Hook was back at the packed out Exmouth Arms, judging a 9 stone boxing competition.

In March it was announced that Hook would fight Felix Scott for England’s black championship title, but whether or not he did, I cannot determine. We do find him, however, engaged in a music hall tour across the country, performing a comedy sketch, “causing much merriment”, based on boxing at the Oxford Palace of Varieties and more. He appears alongside the “lady light-weight” Miss Alice Daultry (variously Daultray, Daultrey or Daultry) with Corporal Higgins, and a number of musical acts, cycling and rollerskating tricks and comedians.

Graeme Kent’s Boxing’s Strangest Fights has an interesting chapter titled Fighting Ladies where we meet Daultry and Higgins in the late 1870s. Higgins was actually Joe Daltry, brother of Abe Daltry, a prize fighter, runner, and instructor at the German Gymnasium (now a fancy restaurant). Abe toured the halls with a female boxer named Selina Seaforth and Joe (as Higgins) before the brothers fell out over money and top billing. Joe went solo, still as Higgins, and took on his own lady pugilist with a slightly altered version of the brothers’ surname – Mademoiselle Daultry. Abe and Joe then begun a war of words in the newspapers, slagging each other and their accompanying women “champions” off in a long-running rivalry. Selina and Mademoiselle Daultry, who I believe to be Alice, are said to have never met in the ring.

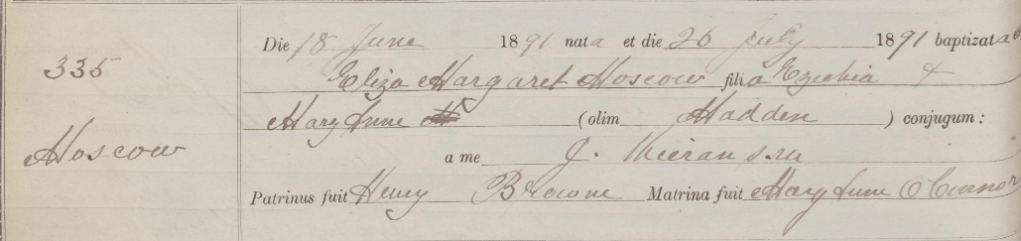

In the summer of 1890, Hook returned to George Belmont’s “booming, blooming” Sebright. He also managed to win his heat in the final of a 100 yard dash in aid of the London and South Western Railway Servants’ Orphanage (£58 raised in total) and found the time – as Hezekiah Moscow – to marry a Mary Ann Maddin (an Irish surname) in Whitechapel. On the 18th June 1891 their daughter Eliza Margaret Moscow was born, then baptised as a Roman Catholic in July.

The Era, on its music hall gossip page, reported on Saturday 17 January 1891 that “Mr Ching Ghook, of Daultray, Higgins and Ching Ghook, sketch artists” – travelling with a theatre company – had been laid up in the Leicester Infirmary with abscesses in his thigh, following an appearance at the Gaiety Palace of Varieties. He was discharged in February and afforded a benefit by George Wilson of the Wells’ Rooms, Bay Street, Leicester, at which he was well enough to perform amidst a line-up of local talent who mostly “lost their heads and went in for slogging tactics.”

It is in 1891 that we find Hook – as Hezekiah Moscow – in his only census appearance: aged 29, ‘a traveller’, and originally from the West Indies. Mary Moscow was 32, born in Bermondsey, and they were living at 36 Elder Street, Norton Folgate, East London. The building was home to several other couples and solo lodgers, who variously worked in the laundry trade, as waistcoat makers, printers, hawkers and newspaper vendors.

In June 1892, a decade or so after arriving in London and starting his boxing career at the Blue Coat Boy, Ching Ghook/Hook disappears almost entirely from the newspapers. There is no more boxing.

His daughter Eliza begun school on the 2nd April 1895 and Hezekiah’s name appeared in the ‘parent/guardian’ list, comprising mostly of fathers, suggesting that at this point he was still alive and well and living at 36 White Lion Street, Norton Folgate.

A rather sad and mysterious notice from Mary Moscow was printed in The Sporting Life on Friday 8 March 1896:

Would Frank Craig send his address to Mrs Moscow, 15 White Lion Street, Norton Folgate, London, as she is anxious to know any particulars respecting Ching Ghook.

By 1901, Mary was cleaning offices and living with Eliza at number 12, St George’s House, Whitechapel, which was a block of model flats demolished in 1973 and replaced with Sunley House. In the 1901 census, the women appear as Marian Moscow and Elizabeth Moscow, yet have the same ages and birth locations as Mary and Elizabeth and are living just feet away from Mary’s prior home with Hezekiah. I believe them to be the same people, but with mis-transcribed or deliberately altered new names – a family tradition, it seems.

The census lists Mary as a widow.

This section has been updated following this very helpful observation by historian John J Johnston!

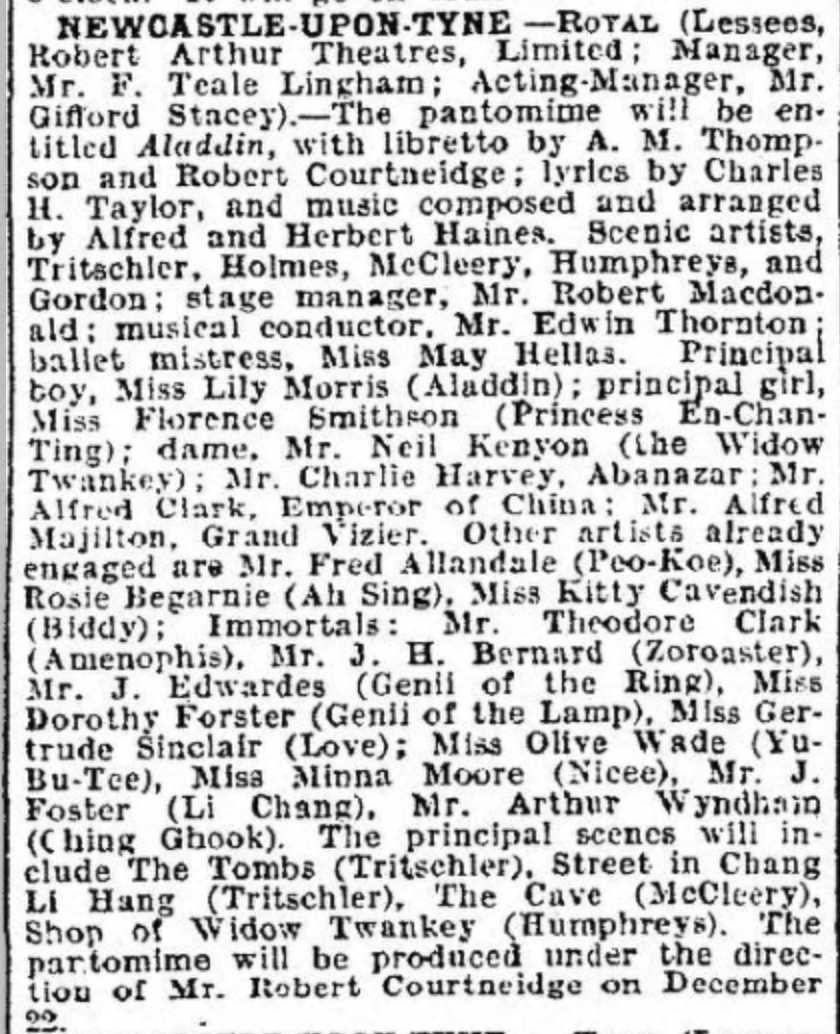

There is a further reference to be found to a ‘Ching Ghook’ in the newspapers, alongside a handful of passing references in much later articles, which look, for example, at the life of his contemporaries. While originally I thought I had found Hook/Ghook in Newcastle in 1906 acting in Aladdin as a character called Arthur Wyndham, it turns out that I can’t read properly, and an actor called Arthur Wyndham was actually playing a character called Ching Ghook. The character name could be a coincidence, or it is possible that the writer had known Ghook or seen him fight, and named the character after him.

I have not been able to find any hospital records, death records, grave or cremation reference, or an obituary for Hook, Ghook or Moscow, Mosco, Mascow or any other variation.

In the Tower Hamlets workhouse admission and discharge lists for 1908, Mary Ann Moscow, aged 49, is described as “Widow of Hezekiah” and a “tailors dresser” living at 30 College Buildings – a block of flats built in the 1880s and run as a co-operative. This excellent blog on Whitechapel history tells us more about what her home would have been like. Listed among the scabies, bronchitis and “mental” patients, Mary was suffering with a septic wrist. Admitted just before Christmas, she was discharged on the 7th January 1909. In 1911, Mary and 19-year-old Eliza were working as office cleaners, as they had been a decade earlier, while lodging with a Solomon and Annie Aarons and their child on Commercial Street. I believe Mary died in 1939.

The 1904 article I referred to in the first part of Hook’s story, which detailed the way he acquired his nickname, concludes its introduction with the suggestion that Hook’s career was cut short by women and alcohol. Could this have caused an early death too?

“Ching turned out to be a useful customer at around 9 stone… but the combined fascinations of the fair sex and the pewter pot, added to our trying climate, caused his career as a boxer to be of somewhat brief duration.”

Where did you go, Ching Hook, Ching Ghook, Hezekiah Moscow – the immigrant who became a pub pot wash boy who became a boxer, lion tamer, boxing club manager, singer, music hall artist, husband and father?

Sorry to leave you with an unsatisfactory finale, but the only answer I have come up with to date is that… he disappeared into thin air. I will keep trying to find out what happened and hope to trace descendants through Eliza Moscow, who I believe may have married and become Eliza Thompson. If you are a much better historian than I and uncover anything that may help, I would be very happy to hear it.

Thank you for reading. We’ll be back to the wrestler Jack Wannop’s story in the very near future.

READ THE UPDATED ENDING (OF PART II)

<<READ PART III>>

Can I ask if you have checked the ‘39 register for Eliza?

LikeLike

Hello. I have! I’ve found a record for an Eliza M Moscow marrying a Henry F Thompson in 1938, London, when she would have been in her 40s. In 1939 they’re living on Summerhouse Drive in Kent. She’s ‘unpaid domestic’ and he’s a 60yr old retired postman. Given their ages at this point, it doesn’t look like they had any kids, unfortunately.

LikeLike

[…] Part I and Part II of Ching Ghook’s […]

LikeLike

[…] This is the third and final chapter of Ching Hook / Ching Ghook / Hezekiah Moscow’s story. You can read the first part (which includes information about why I’m researching him and what on earth all the name variations are about) here and the second part here. […]

LikeLike

[…] <<READ PART II>> […]

LikeLike

[…] Where Did You Go, Hezekiah Moscow? The Life and Times of Ching Hook (Part II: 1888-96) […]

LikeLike

[…] Where Did You Go, Hezekiah Moscow? The Life and Times of Ching Hook (Part II: 1888-96) […]

LikeLike

[…] Where Did You Go, Hezekiah Moscow? The Life and Times of Ching Hook (Part II: 1888-96) […]

LikeLike

[…] Part II of my Moscow blog series I presented a number of theories about where Moscow might have disappeared […]

LikeLike

I have a question, Could it be Hezekiah did claim the coloured heavyweight title or maybe the championship in another division in 1884, if it is heavyweight this would match up as george godfrey did not fight for the entirety of that year, your research skills are a million times better than mine, so if you have any information that would be invalueable to me

LikeLike

Hi Aidan, thanks for your message! The real Hezekiah never fought for a world championship title of any kind. He was pretty well known and respected in London by the mid 1880s (where he lived until 1892, occasionally coaching and boxing in other cities) and took part in local London ‘championship’ competitions in the 10st or 140lb-and-under category in the late 1880s, but he was never world championship material! His record is very average. I’m not aware of him fighting outside of England although he may have done when he left in 1892: he went to New York then but did not continue boxing under any of his pseudonyms as far as I’ve been able to work out.

The World Coloured Championship was only contested in America between its founding and 1909. I believe Godfrey only fought in the US, mainly New York and Boston over his career. In 1884 Hezekiah was employed as a bear and lion tamer at an aquarium in London and just boxed in his spare time. He definitely never met George Godfrey. Godfrey was light for a heavyweight but Hezekiah was much lighter still (9 and a half stone or something like 132lb). As far as I’m aware, Godfrey held the title from 1883 until he lost it to Peter Jackson in ’88.

As you’ll see when A Thousand Blows airs, the character of Hezekiah has the same name as the real Hezekiah, but while there are small nods to the real guy’s life, it’s very much a work of fiction!

– Sarah

LikeLike